Jeff Koons Looks Back on a Life in the Art World

T&C spoke to the artist in Qatar around the opening of a landmark new exhibition.

Lost in America, Jeff Koons’s current retrospective in Qatar, features 60-some sculptures and paintings. There are golden oldies like "Rabbit (1986)," "Buster Keaton (1988)," and "Balloon Dog (Orange) (1994-2000)" as well as newer works like "Party Hat (Pink)(1994-2019)" and "Ballet Couple (2010-2019)."

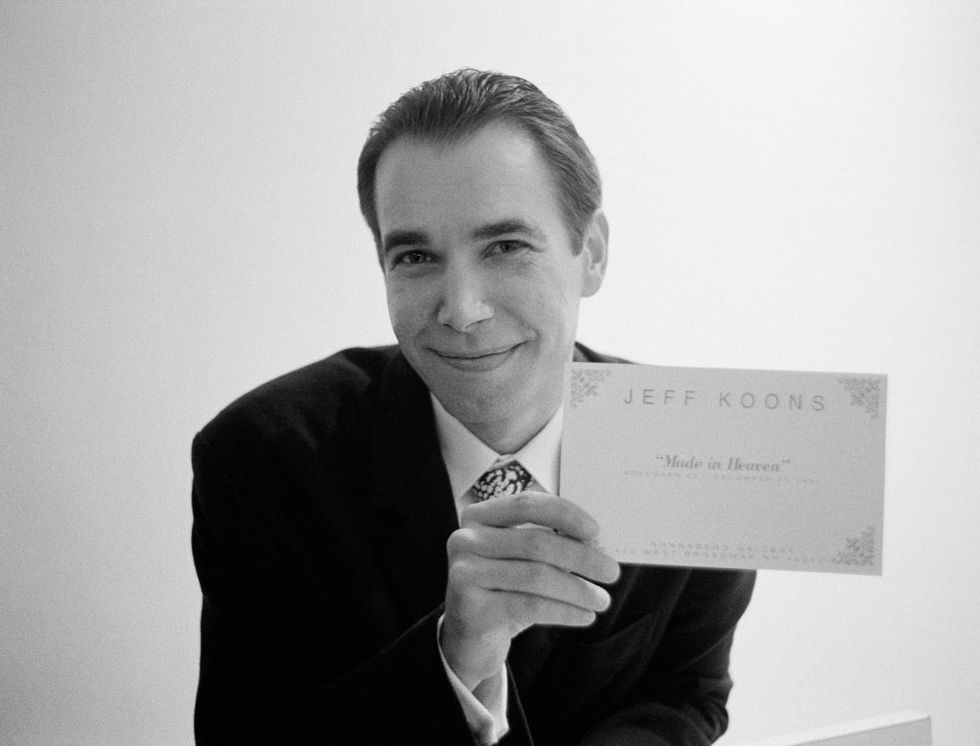

Installed in the ample spaces of Doha’s QM Gallery ALRIWAQ, a stone’s throw from I.M. Pei’s gorgeous Museum of Islamic Art, it’s the 66-year-old artist’s first museum exhibition in a Gulf nation. A photograph of Koons on the cover of the catalogue—he’s posed with crayons and a coloring book in kindergarten—suggests this survey is a visual biography. Curator Massimiliano Gioni of the New Museum rightly believes “organizing something on this scale at this time is amazing.” As it is, due to Covid-19, the show was postponed for a year.

Lost in America traces the way Koons has worked with found objects. Initially, he merely appropriated them. He’d place, for example, two different types of vacuum cleaners in tall acrylic containers. Then, he cast unlikely things like an aqualung or a lifeboat in bronze as if they were baby shoes. The thirty-something artist next took a giant step that catapulted him into superstardom. He transformed a small inflatable bunny into a shiny, stainless-steel sculpture. Balloon dogs became monumental and were fabricated in mirror-polished stainless steel with transparent color coating. All kinds of permutations became possible. Koons turned banal objects into polychromed wood pieces. His son’s Play-Doh inspired a gigantic aluminum mound formed from yellow, green, purple, orange, and blue sections. Not too long ago, two ballet dancers you might find atop a little girl’s birthday cake became large marble figures painted realistically.

Walking through the retrospective, it became apparent that you should expect the unexpected with Jeff Koons.

How did you meet other artists when you came to New York?

By hanging out. I went to restaurants and clubs like Fanelli’s, CBGBs, and the Mudd Club. I always enjoyed interacting and having dialogues about art with other people. I can’t say enough about the ability to communicate with others.

Was it difficult finding a job at the Museum of Modern Art?

I always had to support myself through college. At one point, I was a preparator. I was persistent. Every day I would ask at MoMA if there was a job opening. Finally, they said they needed someone on the membership desk. Besides interacting with people, I was able to study the collection and meet lots of other young artists.

Did you know much about art as a kid?

My dad taught me aesthetics. I had no art history. Later, I learned how it was all connected. My dad was an interior decorator. He stressed how different colors and textures can affect the way you feel. My parents would look at my drawings when I was a child; and then, pat me on my back. In our youth, we don’t make judgements. We just like blue, or we just like yellow.

How critical was your Whitney retrospective?

It was wonderful to have that retrospective. I had been looking forward to it for a long time. Since then, I have continued to work and develop different ideas. Right now, I am involved with my porcelain series. It’s important to get to the essence of your potential.

How has your art changed since the Whitney retrospective?

My art hasn’t changed. If anything, the change has been with me. The Whitney show gave me much needed freedom. I’m interested in how artwork can transform our lives.

Why is your retrospective in Doha called Lost in America?

For starters, I’m American. The work was made in America. Using the name of an Albert Brooks movie left the art open to interpretation. It could mean anything. It references a universal vocabulary.

Has your visiting Doha so much influenced the selection of the art that traveled to Qatar?

We considered the scale of the galleries. We wanted what communicated my work best. It also had to be beautiful.

Are you amazed that "Aqualung," on view in Doha, recently fetched such a huge price at Sotheby’s?

It cost me $9,000 to make "Aqualung." It just sold at auction for $50 million.

How did you get from works like the bronze Aqualung to the Bunny executed in stainless steel?

I like to try things. I see things as opportunities.

Why, after working with bronze and then stainless steel, did you make the Banality series from wood?

I never wanted horizontal development. I preferred a vertical progression. I like to reinvent myself. Everything up to this point was readymade. Then, I realized I cared more about the viewer than the object. I wanted to remove judgement.

In 1992, how did you realize you could make a large puppy from flowers?

I had been spending a lot of time in Europe and was looking at Baroque and Rococo art. I wanted an element that was organic. At the end of the day, you walk away and it is in nature’s hands.

The Gazing Ball Sculptures and Gazing Ball Paintings seem to come out of left field.

When I was a boy in Pennsylvania, our neighbors had gazing balls in their yard. It’s part of my DNA.

TOWN AND COUNTRY