If you teach reading you have probably heard of the “Reading Wars”. And if you haven’t, then perhaps you don’t even need to read any further. For those that have, you might feel confused. I, for example, question why we have to “be at war” with colleagues or pick a side. I don’t want to be at war or pick a side. But the tension on Twitter and Facebook is real.

In essence the debate is about how best to teach reading to students. But many educators wonder if we can believe in both balanced literacy and the science of reading?

In essence the debate is about how best to teach reading to students. But many educators wonder if we can believe in both balanced literacy and the science of reading?

Simply put, yes. Take a deep breath and know that no matter where you stand on these matters, you don’t actually have to pick a side. If you are reading this you are likely in education, possibly an ESL teacher, one that works with literacy, or a combination of both. Welcome.

Let’s visit this extremely heated topic but I want to warn you, I’m not here to spark a debate on which is better. The aim is to focus on English learners (ELs) and how to best serve ELs while they learn to read and acquire English. Most of what’s written on this topic does not have a lens for ELs and that’s what’s been on my mind. I know the Science of Reading. I know English learners. And I know Balanced Literacy.

While some languages are shallow and follow a simple alphabetic principle, English is more complex. It has 26 letters yet 44 sounds and has obscure orthography. Learning to speak it is one thing, but learning to read and write it is a completely bigger challenge. Before most students walk into elementary school, they’ve already heard the sounds, spoken words, and have a nice vocabulary bank stored up. But English learners may not have had those opportunities yet. They may have had different ones, possibly speaking and hearing another language since birth. Some languages have different alphabets, sounds, and words. ELs’ vocabulary banks are not necessarily poorer, they are just different banks. In fact, once these children add English to their bank, they will be richer! In addition to language, kids enter our classrooms with their own sets of background and that background highly affects reading too.

As well-read, knowledgeable educators that know students deeply and have practiced in the classroom, we are able to take theory and research and apply it as students need. Research informs what we do with students. We know how people learn to read, we know how people learn to read in a second language, and we can and should apply that information to lesson planning.

What’s the best way to teach reading?

Here lies the argument. If you ask a dozen people, you’re likely to get varied responses. Some will say through a Balanced Literacy Approach, others will say that the Science of Reading is the only way, and finally some might tell you that neither is right nor wrong but rather to be knowledgeable on both and meet students’ needs. Why are there so many varied responses?

In the end it’s not a war and you don’t have to pick a side. To become lifelong, avid, strong readers students need to:

It’s unlikely that phonics alone will motivate readers. Phonics is necessary, it’s part of the pictures but only part. Motivation is also critical and it’s what keeps readers coming back for more.

What factors should teachers of English learners consider?

Many additional factors come into play when teaching reading to students who are acquiring English. If a child has already “cracked the code” in their first language (L1) reading instruction will differ from that of a child who has not yet “cracked the code” in their L1.

Some other factors to consider include:

In my personal experience as an EL, I entered kindergarten with a large Serbrian listening and speaking vocabulary. Serbian was my first language. We came to America when I was three. And since my parents did not speak English at the time, we spoke Serbian at our home. Stories were told in Serbian, jokes were in Serbian, and even most of the music we listened to for a quite a while was in Serbian. So when I started school, I came with a large Serbian speaking and listening vocabulary bank but a smaller English one. Over time, that balance shifted. I benefited greatly from playing with English speaking peers, collaborative work, listening to my teachers read aloud, vocabulary building, and yes, even explicit and systematic phonics and phonemic awareness. It took awhile for me to “crack the code” and learn to read and write in English.

Older English learners that already read in the first language can transfer that knowledge and the skills they’ve learned when acquiring English. They also benefit from explicit phonics instruction in small groups or one-on-one settings. For example, a third grade newcomer EL from Venezuela may need some additional support with letters and sounds that are non-existent in Spanish such as the sound letters dge make or qu and the letter z. (More on language transfers). Assessing students’ by listening to them read in their L1, asking them questions about their reading life, and/or talking to caregivers about their reading experiences will help to form instruction.

What do ELs need?

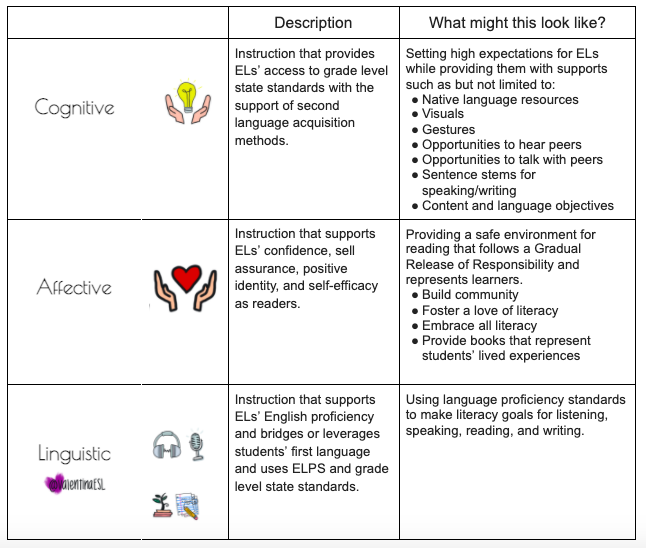

English learners need high quality first teach reading instruction. That means adequate tier 1 reading instruction that is accommodated to meet ELs’ cognitively, affectively and linguistically. Who is responsible for that? ALL stakeholders that serve ELs are responsible for meeting their needs.

Let’s visit this extremely heated topic but I want to warn you, I’m not here to spark a debate on which is better. The aim is to focus on English learners (ELs) and how to best serve ELs while they learn to read and acquire English. Most of what’s written on this topic does not have a lens for ELs and that’s what’s been on my mind. I know the Science of Reading. I know English learners. And I know Balanced Literacy.

While some languages are shallow and follow a simple alphabetic principle, English is more complex. It has 26 letters yet 44 sounds and has obscure orthography. Learning to speak it is one thing, but learning to read and write it is a completely bigger challenge. Before most students walk into elementary school, they’ve already heard the sounds, spoken words, and have a nice vocabulary bank stored up. But English learners may not have had those opportunities yet. They may have had different ones, possibly speaking and hearing another language since birth. Some languages have different alphabets, sounds, and words. ELs’ vocabulary banks are not necessarily poorer, they are just different banks. In fact, once these children add English to their bank, they will be richer! In addition to language, kids enter our classrooms with their own sets of background and that background highly affects reading too.

As well-read, knowledgeable educators that know students deeply and have practiced in the classroom, we are able to take theory and research and apply it as students need. Research informs what we do with students. We know how people learn to read, we know how people learn to read in a second language, and we can and should apply that information to lesson planning.

What’s the best way to teach reading?

Here lies the argument. If you ask a dozen people, you’re likely to get varied responses. Some will say through a Balanced Literacy Approach, others will say that the Science of Reading is the only way, and finally some might tell you that neither is right nor wrong but rather to be knowledgeable on both and meet students’ needs. Why are there so many varied responses?

In the end it’s not a war and you don’t have to pick a side. To become lifelong, avid, strong readers students need to:

- understand the letter-sound relationship

- be able to blend letters combinations

- be motivated to read

It’s unlikely that phonics alone will motivate readers. Phonics is necessary, it’s part of the pictures but only part. Motivation is also critical and it’s what keeps readers coming back for more.

What factors should teachers of English learners consider?

Many additional factors come into play when teaching reading to students who are acquiring English. If a child has already “cracked the code” in their first language (L1) reading instruction will differ from that of a child who has not yet “cracked the code” in their L1.

Some other factors to consider include:

- The student’s first language literacy

- The student’s current English language proficiency

- The quality and quantity of language spoken at home

- The student’s background knowledge and opportunities

- The similarities between written and spoken languages (cognates & written features)

In my personal experience as an EL, I entered kindergarten with a large Serbrian listening and speaking vocabulary. Serbian was my first language. We came to America when I was three. And since my parents did not speak English at the time, we spoke Serbian at our home. Stories were told in Serbian, jokes were in Serbian, and even most of the music we listened to for a quite a while was in Serbian. So when I started school, I came with a large Serbian speaking and listening vocabulary bank but a smaller English one. Over time, that balance shifted. I benefited greatly from playing with English speaking peers, collaborative work, listening to my teachers read aloud, vocabulary building, and yes, even explicit and systematic phonics and phonemic awareness. It took awhile for me to “crack the code” and learn to read and write in English.

Older English learners that already read in the first language can transfer that knowledge and the skills they’ve learned when acquiring English. They also benefit from explicit phonics instruction in small groups or one-on-one settings. For example, a third grade newcomer EL from Venezuela may need some additional support with letters and sounds that are non-existent in Spanish such as the sound letters dge make or qu and the letter z. (More on language transfers). Assessing students’ by listening to them read in their L1, asking them questions about their reading life, and/or talking to caregivers about their reading experiences will help to form instruction.

What do ELs need?

English learners need high quality first teach reading instruction. That means adequate tier 1 reading instruction that is accommodated to meet ELs’ cognitively, affectively and linguistically. Who is responsible for that? ALL stakeholders that serve ELs are responsible for meeting their needs.

Accommodating instruction is the work of the instructor. The teacher that is providing instruction should scaffold and support the students that are being served, ELs and native speakers, students in the GIFTED program, and students receiving special education services. ALL students.

Of Course Phonics!

Kindergarten and first grades are traditionally highly language rich environments (as they should be). Nearly all students, no matter their language experience, are emergent readers and writers. At this very early stage of school, it’s important that phonemic awareness and phonics be explicitly and systematically taught to all learners (Gonzalez & Miller, 2020, p. 127). This helps students learn to “crack the code”. Since reading is not a natural experience, students must be taught to lift letters off of paper, turn them into sounds, connect sounds and make words.

However, learning to decode is not the only part of learning to read. It’s one piece of a large puzzle. Simply decoding is not effective, efficient, or quality reading. Reading includes both decoding and comprehension. And “teachers should not ignore other literacy components such as comprehension and oral language” says Robles (Chalkbeat, 2020).

If we only teach phonics and ignore comprehension, we run the risk of creating students that can decode but lack understanding or interest. When that happens motivation for reading decreases. Students that don’t understand what they read, see little value in reading and may quickly decide it’s not for them.

Kathy Escamilla, author, researcher, and professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder reminds us that “schools must provide both language development and reading instruction for English learners.” When we plan reading instruction we must consider both lens; language and literacy.

It’s not one or the other. It’s What Students Need.

Our goals are to help English learners acquire English proficiency (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) while maintaining their first language. Big goals! But definitely achievable. By creating literacy rich environments that focus on students’ needs, we can meet the goals we set. It’s not one or the other (SOR or BL). Rather, it’s what the student needs. A combination or SOR and BL can support ELs. English learners benefit from phonics, literacy rich environments, literature that is culturally representative, and from pictures.

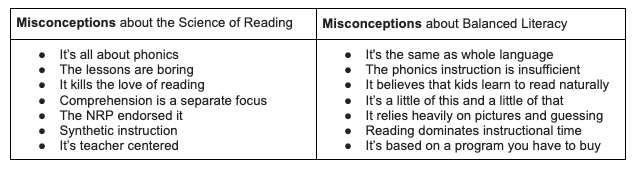

Overall there seems to be misconceptions about the SOR and BL that create tension and pit educators against one another. Some common misconceptions include:

Of Course Phonics!

Kindergarten and first grades are traditionally highly language rich environments (as they should be). Nearly all students, no matter their language experience, are emergent readers and writers. At this very early stage of school, it’s important that phonemic awareness and phonics be explicitly and systematically taught to all learners (Gonzalez & Miller, 2020, p. 127). This helps students learn to “crack the code”. Since reading is not a natural experience, students must be taught to lift letters off of paper, turn them into sounds, connect sounds and make words.

However, learning to decode is not the only part of learning to read. It’s one piece of a large puzzle. Simply decoding is not effective, efficient, or quality reading. Reading includes both decoding and comprehension. And “teachers should not ignore other literacy components such as comprehension and oral language” says Robles (Chalkbeat, 2020).

If we only teach phonics and ignore comprehension, we run the risk of creating students that can decode but lack understanding or interest. When that happens motivation for reading decreases. Students that don’t understand what they read, see little value in reading and may quickly decide it’s not for them.

Kathy Escamilla, author, researcher, and professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder reminds us that “schools must provide both language development and reading instruction for English learners.” When we plan reading instruction we must consider both lens; language and literacy.

It’s not one or the other. It’s What Students Need.

Our goals are to help English learners acquire English proficiency (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) while maintaining their first language. Big goals! But definitely achievable. By creating literacy rich environments that focus on students’ needs, we can meet the goals we set. It’s not one or the other (SOR or BL). Rather, it’s what the student needs. A combination or SOR and BL can support ELs. English learners benefit from phonics, literacy rich environments, literature that is culturally representative, and from pictures.

Overall there seems to be misconceptions about the SOR and BL that create tension and pit educators against one another. Some common misconceptions include:

In his webinar, The Untold Science of Reading, Dr. Jim Cummins (researcher, author, and professor) explains what the National Reading Panel actually found and how their findings have been misinterpreted. Dr. Cummins reminds us that the NRP actually emphasized that “systematic phonics instruction should be integrated with other reading instruction to create a balanced reading program” (p. 2-136). In another webinar, D. Cummins emphasizes the importance of literacy immersion at an early age. Access to an abundance of books. He also discusses the differences between the academic success of affluent students and those less affluent. The leading factor was not phonics but rather early access to literature, print, books-even before preK or kindergarten. He adds that kids get into decoding in different ways and that if they WANT to read and enjoy reading, then they will be primed to learn decoding skills.

Dr. Claude Goldenberg shares in Using the Science of Reading to Improve Literacy Instruction for English Learners the correlation between oral language and reading. He states that “English learners learning to read in English face a more complicated challenge than students who already speak in English.”

One Size Fits None

English learners are not monolithic. We can’t paint them with one brush. And we certainly should not address ELs’ instruction in the same way we would for monolingual students. English learners’ needs are not the same.

“The "Reading Wars" aside, there is general agreement that developing as a reader requires the ability to hear, recognize, and manipulate individual sounds in words (phonemic awareness), grasping the relationship between sounds and letters (phonics), understanding word meaning (vocabulary), reading naturally and quickly (fluency), and understanding what a text is saying (comprehension)” (Tomlinson, 2020).

The bottom line is that it can not be one size fits all. Teaching monolingual students to read is not the same as teaching English learners to read. We have to consider not only the approaches, but also the child in front of us. In education when we are pitted against one another no one wins, certainly not the students we are here to serve.

Related Articles and Resources:

Gonzalez, V., & Miller, M. (2020). Reading & writing with English learners: A framework for K-5. Irving, TX: Seidlitz Education.

Pursuing Clarity in the Science of Reading Debate

Four Things You Need to Know About the New Reading Wars

Direct Instruction in Early Reading

Colorado’s Emphasis on Phonics in Reading Could Hurt English Language Learners

One to Grow On/Invitation to Read

The Untold Science of Reading Jim Cummins

The Critical Story of the Science of Reading and Why Its Narrow Plotline is Putting Our Children and Schools at Risk

Rooted in Reading ASCD

Dr. Claude Goldenberg shares in Using the Science of Reading to Improve Literacy Instruction for English Learners the correlation between oral language and reading. He states that “English learners learning to read in English face a more complicated challenge than students who already speak in English.”

One Size Fits None

English learners are not monolithic. We can’t paint them with one brush. And we certainly should not address ELs’ instruction in the same way we would for monolingual students. English learners’ needs are not the same.

“The "Reading Wars" aside, there is general agreement that developing as a reader requires the ability to hear, recognize, and manipulate individual sounds in words (phonemic awareness), grasping the relationship between sounds and letters (phonics), understanding word meaning (vocabulary), reading naturally and quickly (fluency), and understanding what a text is saying (comprehension)” (Tomlinson, 2020).

The bottom line is that it can not be one size fits all. Teaching monolingual students to read is not the same as teaching English learners to read. We have to consider not only the approaches, but also the child in front of us. In education when we are pitted against one another no one wins, certainly not the students we are here to serve.

Related Articles and Resources:

Gonzalez, V., & Miller, M. (2020). Reading & writing with English learners: A framework for K-5. Irving, TX: Seidlitz Education.

Pursuing Clarity in the Science of Reading Debate

Four Things You Need to Know About the New Reading Wars

Direct Instruction in Early Reading

Colorado’s Emphasis on Phonics in Reading Could Hurt English Language Learners

One to Grow On/Invitation to Read

The Untold Science of Reading Jim Cummins

The Critical Story of the Science of Reading and Why Its Narrow Plotline is Putting Our Children and Schools at Risk

Rooted in Reading ASCD