The United States is the only country in the world that sentences children to life without the possibility of parole. One of those children was a boy named Henry Montgomery. In 1963, Montgomery was 17 years old, and was convicted of shooting and killing a plainclothes police officer in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He was initially sentenced to death, but the Louisiana Supreme Court decided that racial tensions, including Ku Klux Klan activity in the area, had influenced the jury’s decision. Instead, the court resentenced him to life in prison. There is hope, however, that soon he’ll be coming home.

Montgomery is now a long way removed from the teenager he once was. He is 75 years old. He has been in prison at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, also known as Angola, for 57 years.

Sometimes numbers like this exist as abstractions. What does 57 years mean? What are 57 years spent living inside a cage? What they are is a lifetime.

[Brandon L. Garrett: Life without parole for kids is cruelty with no benefit ]

When Montgomery was sent to prison, the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act had yet to be signed. Both Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X were still alive. Ruby Bridges was 9 years old. Four little girls had just been killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. A gallon of gas was 30 cents and a loaf of bread was 20. The Beatles had yet to come to America. “Surfin’ U.S.A.,” by the Beach Boys, was Billboard’s No. 1 song of the year. My own parents, now in their 60s, had yet to begin kindergarten.

Today, according to the Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization that works to reduce incarceration in the U.S., more than 53,000 people are serving life-without-parole sentences. The state of Louisiana, where 70 percent of people serving life sentences are Black, has more people serving life sentences per capita than any other state in the country. Until recently that number included thousands of children, but two relatively recent Supreme Court cases, one of which had Henry Montgomery at its center, changed that. More than 50 years after his original sentence, Montgomery became the petitioner in a 2016 case, Montgomery v. Louisiana, in which the Court ruled that its 2012 decision, Miller v. Alabama—which banned mandatory life without parole for children—could be applied retroactively. The Miller decision was based on research demonstrating that children’s brains are not as fully developed as adults’. This seems obvious and intuitive, but new neuroscientific evidence made clear that children who commit crimes cannot be held culpable to the same extent as adults, and that they have even more of an opportunity to change.

The decisions affected more than 2,600 people who had been sentenced to life without parole, who could now be resentenced.

But simply because someone has had the opportunity to be resentenced doesn’t mean that they will be released. Miller banned juvenile life without parole as a mandatory sentence, but did not ban it outright. So although 800 people who had been previously sentenced to life without the possibility of parole have been released since the Montgomery ruling, more than 1,700 people sentenced as juveniles to life without parole across the country still remain behind bars. And despite the Supreme Court’s assertion that he is “an example of one kind of evidence that prisoners might use to demonstrate rehabilitation,” the petitioner of the case, Henry Montgomery, has remained in prison as well.

One person who is free because of Montgomery’s case is Andrew Hundley, a co-founder and the executive director of the Louisiana Parole Project. Originally sent to prison at 15 years old, Hundley served nearly 20 years in state prisons across Louisiana until 2016, when he became the first juvenile lifer in Louisiana released from prison following the Montgomery ruling. Since his own release, he has been working to get Montgomery and others out of prison. “I feel like it’s my life’s work,” he told me. He was grateful to have been released, but thought that Montgomery should have been the first one allowed to come home. “Henry was in prison for 18 years before I was born. And I’ve been home five and a half years now.”

Soon, Montgomery could join Hundley and the hundreds of other people who became free because of his 2016 case. Next Wednesday, Montgomery is scheduled to go in front of a three-person parole board that will decide whether he will be released or remain incarcerated. This will not be the first time that Montgomery has gone in front of a parole board. He has been denied parole on two occasions, mostly recently in April 2019. In each case, two of the parole-board members voted in favor of release, and one did not. In Louisiana, at that time, parole decisions had to be unanimous.

The parole denial stunned advocates. As the journalist Liliana Segura wrote for The Intercept after the decision, the dissenting vote came from Brennan Kelsey, a physical therapist from Amite, Louisiana, with no background in criminal justice. He was, however, a friend of Louisiana’s governor, John Bel Edwards. Kelsey contended that Montgomery had not participated in enough programs in prison and suggested that this represented “a lack of maturity.”

[Read: A prison lifer comes home]

The problem with this view, as many advocates have pointed out, is that for much of Montgomery’s time in prison, Angola didn’t offer many programs to begin with, and that by the time the prison did start offering programs, it was difficult to change the mindset of many of the men who had been there for decades in a very different environment. “For Henry’s first 20 years there, you just tried to survive,” Hundley told me. “It was the most violent prison in America. There wasn’t this idea of rehabilitation and that prisoners should take part in programming to rehabilitate themselves. That culture didn’t exist, and there weren’t programs. You just woke up every day trying not to get killed.” What’s more, for decades the prison explicitly banned people serving life sentences from having access to educational programming, because the state believed it was a waste of resources.

Regardless of this history, Kelsey announced during the remote teleconference, “Unfortunately, Mr. Montgomery, I’m gonna have to vote to deny you parole.” Montgomery, who uses a hearing aid—which is functionally a box that hangs around his neck like a “repurposed cassette player,” as one reporter described it—didn’t hear what Kelsey had said. His lawyer told him he had been denied parole. He was shocked and confused. Advocates couldn’t believe it. Many were in tears.

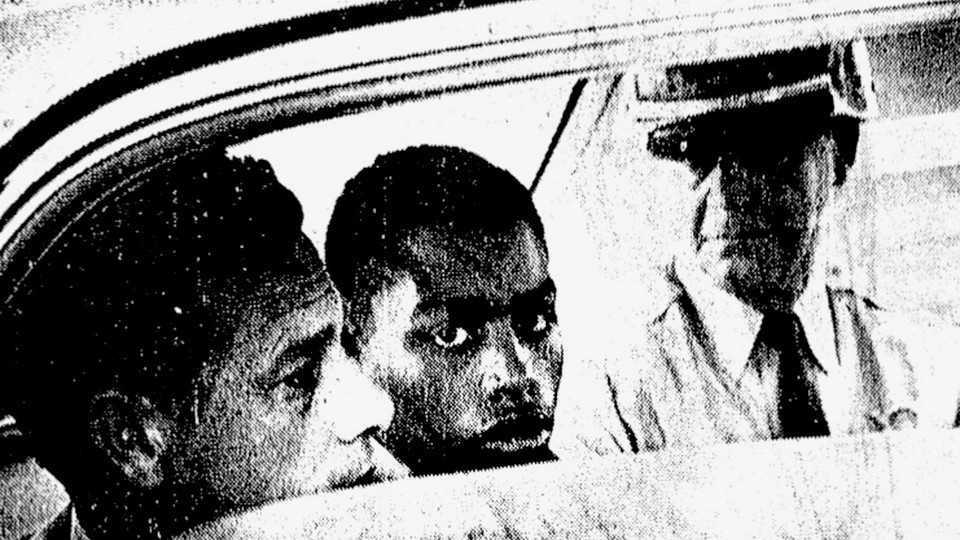

There is a black-and-white 1963 photo of Montgomery from when he was 17 years old, before he was sent to prison. He is sitting in the back of a car in between two police officers. The officer in the foreground is looking straight ahead; the officer on the opposite side is looking at Montgomery. Montgomery, though, is looking directly into the camera. His eyes are large; his face is youthful.

During his trial, the Associated Press reported that Montgomery’s teacher referred to him as “a dull misfit.” But as a former high-school teacher, when I see him, I can’t help but see the faces of the 17-year-old students I used to teach. I take a moment and imagine one of my teenage students being told that they were going to spend the rest of their life in prison. The inhumanity of it is unfathomable to me. And yet, this has been the reality for thousands of young people, many of whom are still in prison today.

Hundley, who is expecting a daughter with his wife and recently received his master’s degree from Loyola University New Orleans, told me that his new life is possible only because of Montgomery, and that he and the hundreds of other former juvenile lifers wake up thinking about him and the impact of his case every day. “So many others have come home and have built new lives and have been successful,” he said. “People who’ve come home to be college graduates. People have come home and started their own small businesses. People have started their own families or married or [become] homeowners or volunteers in the community. I mean, all across the country. There are now 800-plus juvenile lifers who have come home since Henry Montgomery’s U.S. Supreme Court decision, and I think if you had a way that you could study the cumulative impact that these people being home has made on society, it would be mind-blowing to the public.”

Montgomery’s chances for release may be better now than in the past. While previous parole hearings needed to reach a unanimous decision to release someone from prison, earlier this year the policy changed, and now parole can be granted with a simple 2–1 majority (as long as the individual has earned their GED or gotten a waiver, completed anger-management programs, and been designated “low risk” by the Department of Corrections risk-assessment tool, among other qualifying stipulations). Still, advocates like Hundley hope the ruling will be unanimous. They believe that that is what Montgomery deserves, and what he has earned.

There is no good reason for Henry Montgomery to remain in prison, and he should have come home a long time ago. He is not a threat to public safety. He has received only a remarkable 23 write-ups during a nearly six-decade stay behind bars, and his last write-ups—in 2013 and 2014—were for “smoking in an unauthorized area” and “clothes left in his locker box.” He is an elderly man experiencing health problems. He is someone who has an entire network of people ready to step in and help him transition into the final years of his life, and he is someone whose case has served as a source of hope for thousands of incarcerated people across the country. And according to Hundley, “The most powerful thing that happens in prison is when people have hope.” On November 17, the Louisiana Parole Board has the opportunity to free a man who has helped free so many others, and it would only deepen an already profound injustice if it fails to act.