On Tuesday, September 20, 2011, a young patient walked haltingly into a medical office in South Philadelphia to have his bullet wounds examined.

The patient was a 17-year-old named C. J. Rice, who lived in the neighborhood. The doctor was a pediatrician named Theodore Tapper.

My father had been working as a physician in South Philadelphia for more than four decades and had known Rice since he was a child. Rice had been brought in for a checkup soon after he was born, and as a doctor my father had seen Rice several times a year, along with other members of the family. Two weeks and three days before his September appointment, Rice had been shot while riding his bike, in what he believed was a case of mistaken identity. To remove one of the bullets, a surgeon had made a long incision down the middle of Rice’s torso. The wound was then closed with a ridge of staples—more than two dozen. After his discharge, Rice was in severe pain and could barely walk. He needed help to get dressed in the morning and help to go up and down stairs.

When Rice arrived at my father’s office, the wound was still stapled together. Rice slowly lifted himself onto the examination table and winced as he laid himself down. When the exam was over, he slowly pushed himself back up. My father recalls Rice walking out of the office bent over and with short, choppy steps, like an old man.

The timing of that visit is significant because, six days later, the Philadelphia police announced that they were seeking Rice and a friend of his, Tyler Linder, in connection with a shooting that had occurred in South Philadelphia on the evening of September 25 and left four people wounded, including a 6-year-old girl. No guns were recovered and no physical evidence linked anyone to the crime. On the night of the shooting, the victims told the police they had no idea who was responsible. Then, the next day, one of the victims said she had seen Rice sprinting away.

Rice was still recuperating. Thinking the matter would be cleared up quickly, he turned himself in.

I first met C. J. Rice, by Zoom, in February 2022. But I felt I had gotten to know him over the preceding few years through his letters from prison to my father.

Whatever Rice’s expectations, the matter had not been cleared up quickly. To represent him, the court had appointed a lawyer whose attention was elsewhere and whose performance would prove dangerously incompetent. Despite the weakness of the case, Rice was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to 30 to 60 years in prison. Eventually, seeking evidence for an appeal, Rice wrote to my father and asked for help obtaining his hospital records—documents that Rice’s original lawyer appears never to have sought, but which could have underscored his physical condition at the time. My father obtained the records, and the two men kept writing to each other. The correspondence has become important to both of them.

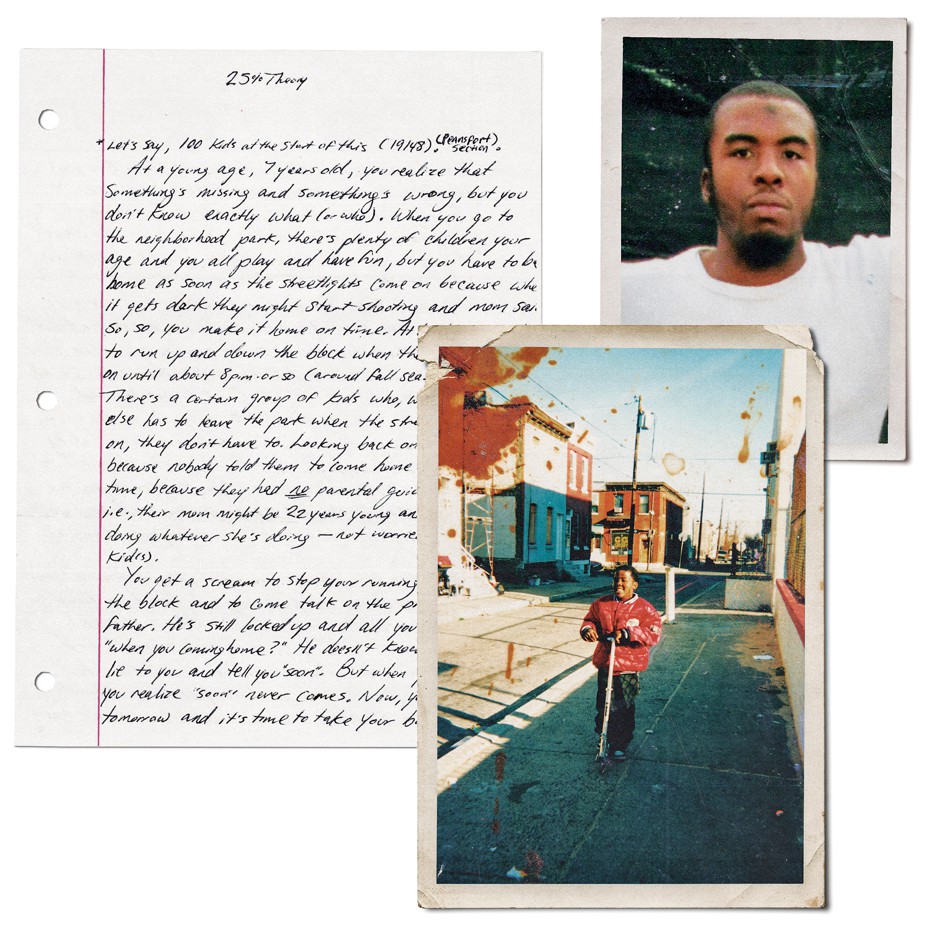

Writing helps Rice pass the time at the State Correctional Institution–Coal Township, the Pennsylvania prison where he is incarcerated. In an angular hand on notebook paper, he reflects on the gravitational pull of what he calls “19148”: the zip code of his old neighborhood in South Philadelphia.

In one letter, he described his childhood:

At the age of 7 you make your first drug sale, oblivious to what you’re actually doing, you’re just following directions to count 13 bags and once you get the money, count out $110 (receiving $10 for yourself). So, imagine that this is all you see, and having it all around you endlessly, could you understand or begin to think that it’s wrong? How can you, when it seems everyone’s doing it in some form or fashion. It seems normal. It is normal. This is how life is lived. This is how money is made. That’s what you think.

In another letter, he imagined a playground scene in which he and his contemporaries were all 7 years old, then went on to describe what happened to that cohort year by year. Violence and crime were rife in 19148, and few were untouched by it. Rice concluded with a summary:

Mir, Sha, NaNa, DaDa, Quan, Keem, Trey, Bird, Heads, Wooka, Jamil, Weeb, Fee, Ovie, E-Man, Veronica, Ern, Mango, Johnny T, Ant, Jeff, Big J, Tez, A.J., Cheese, Zy, Quan (different Quan)—That’s the names that I can think of now (they’re all dead), out of the 27 of them, maybe only 4 of them were older than 25 years old. Maybe another 80 (including myself) who were all struck by gunfire but survived, (all before 21 years old) (some before 18 years old.)

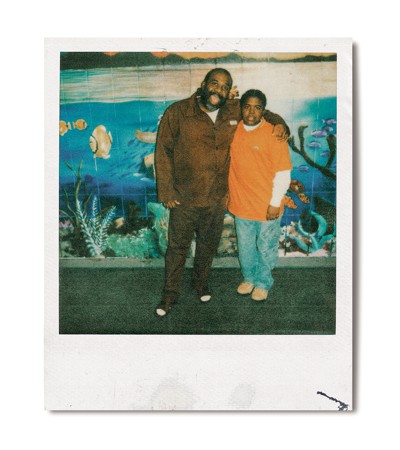

Rice’s father was addicted to heroin and was in and out of prison. By the time Rice was a teenager, he himself was selling heroin and smoking marijuana. Rice was arrested for marijuana possession in 2009, at age 15, and then again in 2010. After one of these encounters with the law, his mother sent Rice to live with his aunt in North Philadelphia for a period of time to get him out of the neighborhood. Despite the chaos around him, Rice did well in school. He had always been bright—in kindergarten, he was reading well above grade level—and by September 2011, at the start of his senior year, he needed only a handful of credits to graduate from high school. He had visited Howard University and sat in on classes at Temple. He thought he might want to become an accountant.

My father, who is now 82, came of age during the 1960s and has always been something of an activist. A graduate of Harvard Medical School, he chose to do his pediatric residency at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and returned there after a period with the public-health service in New York City. He became involved with the Medical Committee for Human Rights—a group founded to provide medical care for people injured in civil-rights protests—and served as the head of its Philadelphia chapter. On the side, he treated sick children at a clinic sponsored by the Black Panthers. In time, he set up his own practice in South Philadelphia. This area is also where he and my mother bought a house, in 1969, when I was three months old. My brother and I grew up there through the 1970s, housing projects half a block away.

My father is an idealist. He is generous with his time. When he makes donations, he usually does so anonymously, on principle. But he is not naive. Having worked in South Philly for more than 40 years, until his retirement, he knows all too well that teenagers, even polite and intelligent ones, are capable of horrific acts. And he knows that Rice’s record is far from spotless. But as a doctor, he believes that Rice’s involvement in the crime for which he was convicted was physically impossible. Over the years, he has supported efforts through a variety of channels—state courts, the district attorney’s office, the governor’s office, federal court—to get Rice’s case reconsidered. Some of these efforts have been exhausted. Some continue. In 2020, as I learned more about the case, I related several of the facts as I knew them in a Twitter thread. Then I began to look deeply into the case myself.

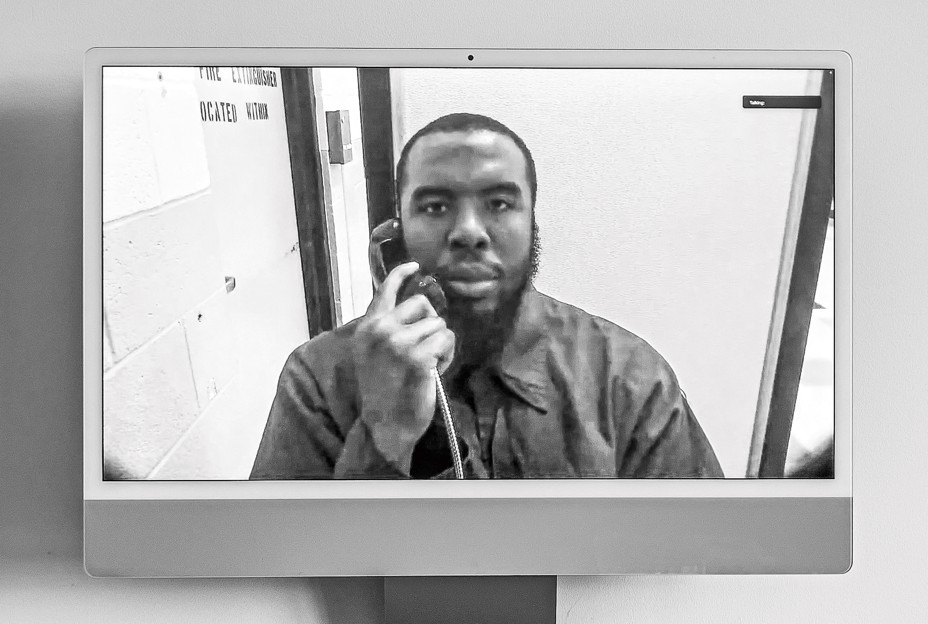

In my first conversation with Rice, he appeared on the Zoom screen wearing a dark-red jumpsuit. He smiled often, and even with a beard his face looked young, though from the neck down, his body was a fortress of prison muscle. He was seated in a visitation booth. In his right hand, he held a phone on a cord, which in normal times connects to a phone for a visitor on the opposite side of a plexiglass window. Now, with an open laptop sitting in place of a visitor, the phone served as the audio conduit for the call.

Our conversation was easy, congenial. But when I began to ask Rice about his case, his speech became staccato and impassioned. He recited police-badge numbers from memory. He provided page numbers for specific passages of testimony in trial transcripts. He recalled each of the very few moments spent with his lawyer. Rice has had more than a decade to think about the steps that led to his imprisonment. He had a lot to say.

[Read: The Supreme Court doesn’t necessarily care if your lawyer is unethical]

The story told here centers on Commonwealth v. Charles J. Rice and the events around that case. Readers will draw their own conclusions about what happened on the night of September 25, 2011. My father and I have drawn ours. There is certainly reasonable doubt—an excess of reasonable doubt—that Rice committed the crimes of which he was accused. But what happened after that night is not open to argument: Rice lacked legal representation worthy of the name. And as he has discovered, the law provides little recourse for those undermined by a lawyer. The constitutional “right to counsel” has become an empty guarantee.

The night of September 25 was unseasonably warm. When Latrice Johnson saw two figures walking up Fernon Street toward South 18th wearing hoodies and long pants, she should have known something was wrong—that’s what she told herself later. The time was about 9:30 p.m. The two figures had their hoods up, the strings drawn tight. On the front stoop of her parents’ house, Johnson was waiting for a food delivery. Her son Kalief Ladson, age 17, sat next to her, cradling her niece, 6-year-old Denean Thomas. Three of her other seven children were perched around them. Latoya Lane, her 23-year-old stepdaughter, was across the street with two more of Johnson’s children and two of their cousins. Some of them were playing basketball. Down the street, on the opposite side, the two figures in hoodies drew handguns and opened fire.

[From the January/February 2018 issue: Can you prove your innocence without DNA?]

Johnson dove on top of the children and shielded them with her body. Bullets ricocheted off the brick facade of the house. At least 12 shots were fired. Then, according to both Johnson and Lane, the shooters ran off. Looking down at Denean, Johnson saw that her niece was bleeding from one of her legs. Some of the children shouted, “Denean is gonna die!”

In a 911 call, placed at 9:36 p.m., Johnson’s desperation is evident from the audio recording. “My niece just got shot!” Johnson yells. Screams are audible in the background. A dispatcher requests an address and then asks, “Ma’am, the person that shot her—what did he look like? Black male? White male?” Johnson replies, “They got on hoodies! They’re Black!”

Police officers arrived within minutes. By then, Johnson knew that not only Denean but also Ladson and Lane had been shot. With no time to wait for an ambulance, Officer Charles Forrest loaded Denean and Johnson into his squad car and sped to Children’s Hospital. As Forrest later testified, he asked Johnson if she knew who had shot Denean and the others. Johnson said only what she had told the dispatcher. She did not identify the shooters.

Arriving at the hospital, Johnson realized that she, too, had been injured; shrapnel had caused lacerations on the lower part of her body. Forrest took her to the adjacent Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, where he again asked if she knew who the shooters were. Johnson’s answers suggested, once more, that she had no idea who either shooter was: “One Black male wearing a gray hoodie and the other with a black hoodie, and they both had black sweatpants.”

Kalief Ladson and Latoya Lane, meanwhile, had also been brought to a hospital. They were visited later that evening by a police officer, Lynne Zirilli. As Zirilli later testified, she asked them if they could describe the shooters. Ladson said only that he had seen “two to three Black males in dark hoodies.” Lane said she had seen “two to three Black males.” They made no identification.

Overnight, however, everything changed. According to the police, a confidential informant relayed a tip: A teenager named C. J. Rice may have been involved. By evening, Johnson and Lane would change their stories. One of them would say she had seen Rice at the scene, and the other would say she had seen his friend Tyler Linder.

For different reasons, both the prosecution and C. J. Rice would contend that the September 25 shooting had to be seen in the context of the shooting three weeks earlier, on September 3, that had sent Rice to the operating room. That afternoon, Rice and Linder had been gambling with friends at an apartment in South Philly. Around 7 p.m., the two boys mounted their bikes and began pedaling toward Rice’s home. Soon, a black Oldsmobile with tinted windows pulled up behind them. By their own accounts, neither Rice nor Linder recognized the car. From a window, shots were fired. Rice was hit three times, in his abdomen and in his left flank and buttock. He recalls feeling as if the left side of his body had been pinched, then bludgeoned by a crowbar. An ambulance rushed him to Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, where a surgeon named Murray Cohen cut into Rice’s abdomen, from the sternum down to a few inches below the navel. Cohen eventually found and extracted a bullet. Fragments of the others remained inside. One bullet had struck Rice’s pelvis, causing fractures. While still in the hospital, Rice contracted pneumonia. Because of other complications, his wound had to be reopened, drained, and closed again. When he was finally discharged, after eight days, he went to stay with his godmother, Deania Duncan, and her family in West Philadelphia, away from the scene of the shooting.

Who had been in the Oldsmobile? Rice’s mother, Crystal Cooper, told police about a rumor that the perpetrator was someone named “Noodle.” Investigators noted in a report that “the reliability of this information is questionable.” On September 16, Duncan drove Rice—mainly housebound, barely able to walk—from her home to a police station in South Philadelphia. Cooper, who worked in the district attorney’s office and knew many officers on the force, hoped that her son would give a statement. But the relationship between youths in the neighborhood and the Philadelphia police force has long been one of deep hostility. The kids Rice grew up with had an unwritten rule: When you saw the police, you ran. Rice declined to say anything, explaining that he didn’t know who had shot him and wouldn’t tell the police anyway; if he’d done so, he told me later, he “might as well just pack up and move to Texas.” The police report notes that Rice had come downtown only “because his mother dragged him there.” Rice remembers a detective named Robert Spadaccini—who had worked with his mother for years—telling him that the “word on the street” was that Kalief Ladson had been the shooter, and cautioning Rice, with a wave at the squad room, that “if anything happens to him or to his family or anyone close to him, they’re going to come for you first.” Rice recalls pulling up his shirt, showing Spadaccini his stapled wound, and saying, “I won’t be doing anything.” (Detective Spadaccini could not be reached for comment.)

Rice told me that, other than the trip to the police station, he rarely left Duncan’s home. He remembers once visiting his girlfriend, whose mother had just died. And he made the trip to my father’s office, to have his wound looked at.

Rice was in constant pain, but as my father recalls, he was adamant about not taking painkillers—he had an aversion to them. Both men recount their conversation in his office the same way:

“You’re due for a refill,” my father said, referring to the prescription for Percocet the hospital had provided.

“I’m not taking the pills,” Rice replied. He hadn’t taken any since the second day of the prescription; he didn’t need a refill.

“Why not?” my father asked.

“I don’t like the way they make me feel,” Rice said—lazy and spaced-out.

“If you’re feeling enough pain, I think you should take them,” my father urged. But Rice said he was going to tough it out.

It wasn’t just the evident pain that made my father believe that Rice couldn’t have sprinted from the scene of the shooting. My father wasn’t yet aware of the fractures in Rice’s pelvis—that information was in hospital records, which he hadn’t seen—but in his view as a doctor, the totality of Rice’s condition argued against the capacity for strenuous exertion. Rice had just recovered from pneumonia. He had lost muscle strength because of prolonged immobility. And he still had staples in place on the long abdominal incision—they weren’t due to be removed for another week. “I don’t think it would have been physically possible,” my father told me. “He could not have run away.” In the hands of competent counsel, the issue of Rice’s physical capability by itself would have raised serious questions about his involvement.

But the September 3 ambush would also become central to the police narrative, though no evidence to support that narrative was ever presented in court: In the eyes of the police, if the “word on the street” was credible—if Kalief Ladson had staged the ambush—then Rice and Linder had a possible motive to strike back.

The September 25 shooting received significant media attention, and not only because one of the wounded was young. Philadelphia was on track to finish 2011 with the highest per capita murder rate among large American cities. Although no one was killed in this shooting, people were concerned about guns, gangs, and drugs. The Philadelphia police were under intense pressure to clear cases and take shooters and their weapons off the streets.

Nothing is known about the confidential informant who conveyed the tip pointing to C. J. Rice, or about exactly when the tip was received or what the informant alleged. On September 26, after receiving the tip, the police ran Rice’s name and the names of the victims through their “shooting database.” The database noted that Rice, while on his bike with Tyler Linder, had been shot a few weeks earlier. According to the database, Rice was a purported member of the so-called 7th Street gang. Ladson was a purported associate of the rival 5th Street gang. He also was mentioned as a suspect in the earlier shooting. Had they all been involved in a gang feud? If so, maybe Ladson had been the target of a retaliatory hit; Johnson, Lane, and Denean just happened to get in the way. This idea is floated in the police investigation of the September 25 shooting. But the investigation documents contain no supporting evidence for any of this, and none would be presented at trial. Whatever the police may have said to Rice regarding the attack on him—and whatever the police may have thought—no speculation appears in the official investigation of the events of September 3.

C.J.’s early life. He died in 2013. (Courtesy of Crystal Cooper)

Nonetheless, they had a theory. Detectives John Craig and Neal Aitken printed photo arrays that included pictures of Rice and Linder. At the time, the Philadelphia Police Department was still three years from adopting what has become a widely accepted best practice for reducing bias in witness identifications—the “double blind” method. Made official policy under Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey in 2014, the double-blind method ensures that the officers showing witnesses possible perpetrators, either in photographs or in a traditional lineup, are unaware of which individual is the suspect. In this instance, Craig and Aitken knew exactly whom they were looking for—they were the officers on the case.

The day after the shooting, the detectives visited Latoya Lane and then Latrice Johnson. The interviews, conducted at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, were crucial to the investigation. Because the guns used in the shooting were never found and no physical evidence tied the crime to any individual, an eyewitness identification of a potential suspect would carry immense weight in court. Indeed, it would be the only evidence. Although Lane and Johnson had said to police on multiple occasions that they did not recognize either shooter, they responded differently during the hospital interviews. Eyewitness accounts do change; fear or trauma may color initial statements. Judging from the interview record, explanations for the new accounts by Lane and Johnson went unexplored. The document invites questions.

[Barbara Bradley Hagerty: The other police violence]

There are no verbatim transcripts of the interviews because there were never any audio recordings. The conversations were only partially preserved, in handwritten notes. From passing references—an allusion to something that occurred in the interview but that is not actually recounted in the notes—it is clear that things were said that were never written down. Detective Craig, who took the notes, later acknowledged that they are imperfect and incomplete.

Craig and Aitken started with Latoya Lane, who was still receiving inpatient hospital care. Craig’s notes contain no information about a preliminary exchange, though there must have been at least an introduction. The notes officially begin with a question from the detectives about what had happened the night before. Lane said that when she’d heard the shots, she’d turned to run toward the stoop. “That’s when I saw Tyler,” she said. “I seen the spark coming from his hand.” Neither Lane nor the detectives ever use Tyler Linder’s last name, and the detectives never ask for it—it’s as if Linder had already been discussed in a missing earlier part of the interview. It is not known how his name was first brought up. As it happens, Lane knew Linder; he was a friend of a cousin. She said she had seen another person running across the street, also wearing a dark hoodie, but hadn’t glimpsed his face. Later in the interview, the detectives handed Lane a photo array and asked, “Do you see Tyler here?” She replied, “Right here”—not surprising, because she knew him. With a pen, she circled a headshot of Linder in the top row of the grid, second from the left, and signed her name.

Next, about three hours later, the detectives interviewed Johnson. She had been released from the hospital but had returned to visit Lane, and the detectives met with her there. Before the detectives arrived, Lane and Johnson had talked about the case, and Johnson knew that her stepdaughter had given the detectives Linder’s name.

In the interview with the detectives, Johnson, like Lane, changed her story. The police notes indicate that Johnson was shown a photo array before the interview began, but they contain no account of that process. She circled and signed the bottom-right headshot, a picture of C. J. Rice. As had been the case with Lane, Johnson knew the person whose picture she circled. Rice had gone to school with her son Kalief; she and Rice were friends on Facebook. It is not recorded what question from the detectives prompted her to circle his photo. The written account is at times both precise and slightly mysterious. It begins with “My name is Det. Craig & this [is] Det. Aitken,” as if the detectives had not introduced themselves during the earlier, missing part of the interview, when they showed Johnson the photo array. In any case, Johnson thought back to the night before, placing herself on the stoop and describing how she’d watched two hooded figures approach. “Then I saw C.J. shooting in our direction,” she said, according to the notes. “It was loud as shit.”

Johnson insisted to Craig and Aitken no fewer than six times that Rice was the person who had shot her. She did not explain why, when asked on three previous occasions, she’d failed to identify someone she had known for years. Aitken, since retired and recalling the two interviews a decade later, had only a hazy memory of them. According to the notes, Aitken and Craig did not press Johnson or Lane about how their inability to identify the perpetrators had become a solid identification overnight. (A spokesperson for the Philadelphia Police Department suggested that it was not uncommon for eyewitnesses to hesitate before cooperating with police but declined to comment on other aspects of the interviews.) Aitken told me that Johnson’s identification of Rice fit the narrative the detectives were already working with—that the more recent shooting was related to the earlier one and had been spurred by revenge.

The police had the eyewitnesses they needed and secured arrest warrants for Rice and Linder. The pair had acted together, as a team—that was the official theory.

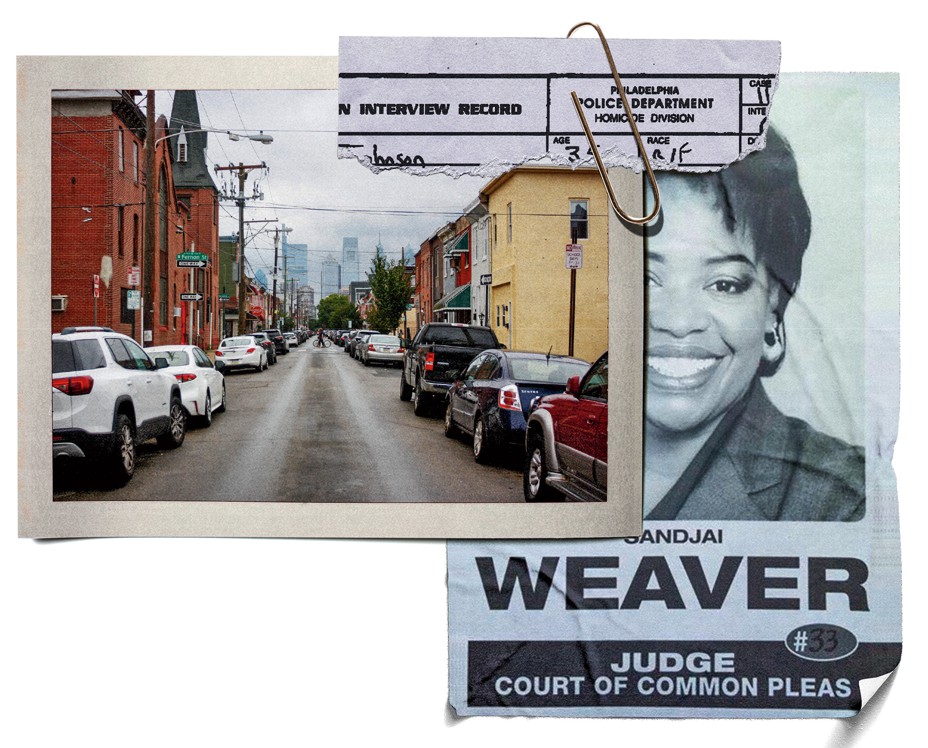

Crystal Cooper learned that her son was wanted for attempted murder on the following day, September 27. Cooper called Deania Duncan, who drove Rice back to the police station in South Philadelphia; Cooper met them there. Rice walked into the building with what Cooper told me were “baby steps.” Outside the station, she called a former colleague, Sandjai Weaver, then working as a defense attorney. As Cooper listened on speakerphone, Weaver cautioned that Rice should say nothing to the police without her present. She promised to hurry over.

As he was booked, Rice made a point of showing his wound to a detective, the staples still sealing the incision. He handed over his cellphone, believing its location data would prove that he hadn’t left West Philadelphia on the day of the shooting. Duncan explained to the police that she had information about Rice’s whereabouts at the time of the shooting and hoped to make a statement.

The intended statement was straightforward, and her family could vouch for it: Rice had spent all of September 25 with Duncan’s son Quadifi, then 14, watching the Jamaican gangster film Shottas over and over again; at the actual moment of the shooting, Rice had been at home with Quadifi, Duncan’s father, and her 7-year-old son, Rickey. The arrest, she said, had been a mistake. “He had to keep a pillow on his abdomen,” Duncan told me later. “His wounds had to be cleaned and changed daily. The way my house is, it was too many steps for him to be able to walk. It made his wound bleed out more, and he could barely stand up or even walk.”

But no one took a statement from Duncan. She says an officer at the station told her she wasn’t needed and sent her on her way. Waiting for Weaver, and following her instructions, Rice said nothing, not even explaining his alibi. And he never got the chance, because for whatever reason, Weaver failed to show up. In the middle of the night, Rice was transferred to the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center.

Like Rice, Tyler Linder had an alibi; unlike Rice, he had video to support it and people in his corner, including a lawyer, who made sure the alibi was formally recorded. On the night of the shooting, Linder and his brother had been helping their mother clean a facility in Northeast Philadelphia. He had swept and mopped until at least 10 o’clock, he said, and security video could probably prove it. Linder’s mother had enough money to enlist the services of Raymond Driscoll, a defense attorney at Levant, Martin & Tauber, a small practice in the city. Eventually, Linder made bail. He and his mother and brother had sat for alibi interviews with the police soon after the arrest. A month later, Linder’s mother and Driscoll pressed to arrange a second round of interviews with the D.A.’s office.

Cooper lacked the money to make bail for Rice, so he would remain confined while awaiting trial like any other criminal defendant without resources—one of hundreds of thousands in this situation at any moment. Rice would not go on trial for more than a year. For legal counsel, Cooper looked to Weaver. “Sandjai worked in the office next to my mom’s since I was 5 or 6,” Rice told me. “I knew Sandjai almost my whole life.” In 2005, Weaver had mounted an unsuccessful bid for election as a Court of Common Pleas judge. A 12-year-old Rice had handed out campaign flyers. Cooper doubted she could afford Weaver’s services for very long, but in December, Weaver was granted a formal court appointment to represent Rice, allowing her to be compensated with public funds.

[From the June 2022 issue: Can forensic science be trusted?]

She met with him for the first time that same month, in advance of his preliminary hearing. Determined to participate in his own defense, Rice asked Weaver to send him copies of the pretrial discovery documents—all of the evidence that the prosecution intended to present. Rice wasn’t sure what to look for, but an older man detained with him had advised that the discovery was everything: If there was something that could clear his name, it was bound to be in those documents. Later, Rice also asked Weaver to subpoena his Cricket Wireless phone records. The location data, he said, would back up his alibi. Weaver promised that she would do both.

The formal appointment of Weaver as counsel may have seemed like a blessing. Rice and his mother did not know that Weaver was in deep financial distress and seemed to be taking all the freelance work from the courts that she could get.

Court-appointed private lawyers and public defenders are not the same thing. Public defenders are salaried professionals who make a career representing the indigent. In Philadelphia, public defenders handle one out of every five murder trials. Courts must appoint private attorneys to take on the remaining 80 percent. Philadelphia is by no means an outlier: The great majority of people in the U.S. live in jurisdictions that rely on both the public-defense bar and appointed private attorneys. In Philadelphia in 2011, court-appointed lawyers received flat fees: $2,000 for preparation if a case went to trial, and $1,333 if it didn’t. For each day after the first day of trial, court-appointed lawyers received $400 a day if they spent more than three hours in the courtroom and $200 if they spent fewer.

These rates were extremely low, especially for cases involving murder or attempted murder, which are among the most challenging a lawyer can take on. Such meager compensation shrinks the pool of available attorneys and reduces its quality. Research suggests that, on everything from conviction rates to severity of sentences, appointed lawyers are far less successful than public defenders. The flat fees also create a perverse incentive. Whether attorneys spend 10 hours preparing for trial or 10,000 hours, they’ll be paid the same small amount. It’s in their interest to maximize their caseload and minimize their prep time.

Weaver was profoundly subject to these pressures. Nine months before her appointment as Rice’s lawyer, she had filed for Chapter 13 bankruptcy. On March 16, 2011, Weaver declared that she had only $400 in her two bank accounts. She owed creditors nearly $130,000, not including her mortgage, which she was behind on. As a condition for debt relief, Weaver was required to submit a rigorous accounting of her anticipated income and expenses—her “Chapter 13 Plan”—which would determine how much she paid back to a bankruptcy trustee each month. In her first proposed plan, Weaver declared $4,000 in monthly income and $3,245 in expenses, and she proposed paying creditors $750 a month for 60 months. That wasn’t good enough, so Weaver submitted a second plan, agreeing to pay $1,261 every month. To make these payments, she would have to earn more money than she had initially thought possible.

A judge approved Weaver’s Chapter 13 Plan on September 20—the same day Rice came into my father’s office, and just a week before his arrest.

Between the preliminary hearing and the opening day of the trial—a period of 14 months—Weaver met with Rice only twice. Both meetings took place at the Philadelphia Industrial Correctional Center. Neither lasted longer than 15 minutes. Rice tried frequently to reach Weaver by phone, initiating all the calls himself; she had no answering service, and he succeeded in reaching her only three times, again speaking to her for no more than 15 minutes on each occasion.

Weaver did not bring Rice a copy of his discovery, but she did come to the meetings carrying what looked to be a large stack of other people’s case files—Rice suspects she had arranged for a marathon series of client meetings at the prison. Rice’s two meetings with Weaver were too brief for any meaningful discussion of trial strategy. Rice reminded her to send over his discovery and get his phone records, which she had not yet done. They were essential. She promised that she would.

Not until April 26, 2012—seven months after her client’s arrest—did Weaver submit a notice of alibi for Rice to the district attorney’s office. In it, she listed all the members of Deania Duncan’s family who lived at her home in West Philadelphia. She stated that Rice had always been at home, with at least one of them, on the day of the shooting. She provided their phone numbers. But unlike Tyler Linder’s attorney, Weaver didn’t make arrangements for alibi witnesses to be interviewed. The burden thus fell on the D.A.’s office to find the alibi witnesses.

When I obtained a copy of Weaver’s notice of alibi, it had been heavily annotated by someone at the D.A.’s office. In the margins, notes in looping cursive recorded a call to the Duncans’ home phone on May 15; there was no answer and no answering machine. The office tried the next day and reached a man—in all likelihood, Duncan’s father—who said he was going to a doctor’s appointment and would call back. The office tried three more times, then seems to have given up. Duncan told me that Weaver made no effort of her own to contact her or other family members in order to take their testimony. As a result, the first time an alibi witness provided an official statement of any kind in support of Rice was in the courtroom, 16 months after the shooting. This negligence would be used by the prosecution to cast doubt on the alibi itself.

In the meantime, the official theory of the case hardened. The September 3 shooting that had sent Rice to the hospital remained unsolved, but the police embraced the assumption that Latrice Johnson’s son Kalief Ladson was the shooter in the Oldsmobile. A further assumption was that Ladson had been retaliating for some previous event. As prosecutors saw it, the tit-for-tat scenario gave Rice and Linder a motive to come after Ladson. Both men dispute the idea that Ladson was the shooter. They were all friends from school, Rice told me. He thinks the shooting was a mistake—that he and Linder had ridden their bikes into the center of some unrelated beef. Medical notes from his hospitalization immediately after the September 3 shooting record that Rice told a nurse that he “does not think he was the intended target.” Rice and Linder also deny that they were members of a gang. “The way they classified it,” Rice told me, referring to the police, “a gang was everybody you went to school with or everybody that you might have played basketball with.” But there were indeed gangs, and for youths in some neighborhoods they could be hard to avoid. What is certain is that official police files and backup documents furnished in discovery contain no supporting evidence for the gang-feud theory that drove the investigation, or for Ladson’s involvement in the September 3 shooting. No evidence for any of this was ever presented in court.

As the trial date approached, Eric Stryd, the assistant district attorney assigned to the case, privately expressed doubts about the police theory that Rice and Linder had acted as a team. As explained in an internal memo I obtained, the case against Linder could prove hard to make.

Video footage largely backed up Linder’s story. It had shown him cleaning a facility in Northeast Philly until at least 8:45 on the night of the shooting. He and his mother said they had then gone on to clean another building; it had no security camera. Additional video evidence showed an SUV matching the description of his mother’s leaving the area at 9:53, though the video was inconclusive because a license plate was not visible. Linder might have skipped out at 8:45 and gotten a ride to the crime scene in South Philly, and his mother and brother could have been covering for him. But accepting the whole scenario could be a lot to ask of a jury. Rice’s alibi, however, was still unverified, and likely to be less sturdy.

[Read: How two newspaper reporters helped free an innocent man]

In a summary of the overall case, under the rubric “Additional Facts,” the internal memo states, “Victims could not tell the police at the scene who did the shooting.” Under the rubric “Problems,” the memo states, “Victims both can ID only one of the two defendants and they do not tell police/nurses immediately who shot them.”

Coming back, in a different document, to the potential difficulty of proving Linder’s involvement, Stryd asked, “Is there strategic value to getting rid of the weaker case and just go forward on the stronger one?” Stryd said he was “torn about what the best way is to proceed.”

In the D.A.’s office around that time, there was a phrase prosecutors sometimes used: “Just put it up.” In other words, just prosecute and let the jury decide. Whatever the thinking, in the end, the D.A.’s office elected to put both Linder and Rice on trial.

Eric Stryd today works in the office of the state attorney general. In an emailed response to questions, he said he was unfamiliar with the phrase “Just put it up.” He confirmed his uncertainty about the case against Linder.

Of course, giving credence to Linder’s alibi would have called into question the police theory that Rice and Linder had been partners, acting out of revenge. If Rice was one of the shooters, then his partner must have been someone else.

In his emailed response, Stryd wrote, “I was instructed to proceed to trial.” His supervisors, he noted, were “more senior and more experienced than I was.”

C. J. Rice and Tyler Linder were tried together, but they were represented by different lawyers. The case against both was thin. As much as anything else, Rice was up against the performance of Sandjai Weaver.

Right off the bat, Weaver had failed to move to decertify the case to juvenile court, even though Rice was a minor who had no prior violent offenses. (Linder was 19, and did not have this option.) On the trial’s first day, Weaver was admonished by Judge Denis Cohen for arriving in court with unlabeled exhibits and no copies for the bench.

Because there was no physical evidence, the prosecution’s case against Rice rested entirely on the testimony of Latrice Johnson, the sole eyewitness to place him at the scene. That she had not identified him when initially asked, on three separate occasions, opened an array of avenues that Weaver could have exploited, but did not.

To begin with, Weaver could have challenged the way the photo arrays were presented during the hospital interview. More crucially, she could have raised significant doubts about Johnson’s ability to see Rice from the stoop where she was sitting—if she’d been familiar with the crime scene. Johnson affirmed on the stand that the sidewalk where the shooters had stood was approximately 20 feet from the stoop, and that her view of the perpetrators in the darkness was aided by a streetlight. In fact, the distance was more than 60 feet. And there was no streetlight at the spot where the shooters were said by the witnesses to be standing; the closest one was across the street. There would have been ambient light from other sources, but the physical distance was a real problem: From the stoop, it’s difficult to make out someone on the corner—a person looks very small—and it would have been harder at night with a hood drawn tight around the person’s face. There were also two cars obstructing the view of the corner from the stoop. The crime-scene diagram created by the police, which was included in the first few pages of the discovery documents, made most of this clear. A few measurements would have filled in the gaps. But Weaver said nothing, so jurors never knew. Left uncorrected, Johnson’s erroneous description of the crime scene was the crime scene.

By contrast, when Raymond Driscoll, Linder’s attorney, cross-examined Latoya Lane—the only eyewitness placing Linder at the scene—he so vigorously challenged the inconsistencies in her testimony that she broke down, collapsing in tears after saying, “When I was in the hospital, when they came, I was on medication, so, like …” The judge had to call a recess, and ultimately stopped the trial for the day.

Although jurors give significant weight to eyewitness identification, experts agree that eyewitness testimony is highly unreliable. More than two-thirds of the Innocence Project’s 375 DNA exonerations involve eyewitness testimony now proved to have been wrong.

At the time of Rice’s trial, defense attorneys in Pennsylvania were legally prohibited from calling experts to testify about the unreliability of eyewitness testimony—a prohibition lifted by the state supreme court only in 2014. Still, a 1954 case in Pennsylvania, Commonwealth v. Kloiber, allowed attorneys to ask a judge to explain the limits of an eyewitness’s identification in situations where a witness did not have an opportunity to clearly view a perpetrator, had struggled to identify him or her, or had a problem making an identification in the past. Given the circumstances—the hood, the darkness, the distance—and the fact that Johnson had failed to identify Rice the first three times she was asked, her testimony could have merited a “Kloiber instruction.” Weaver never requested one.

Instead, she got into a long and meaningless exchange with Johnson, consuming pages of transcript, about where to locate a basketball hoop on a whiteboard diagram. At one point, confused and frustrated, Weaver seemed ready to throw in the towel: “Sorry, Ms. Johnson, I’m not familiar with your area,” she said.

At the defense table, Rice remembers covering his face with one of his hands. Weaver, he now understood, had never visited the street where the shooting took place. And he himself lacked the knowledge to correct her—despite her promise on two occasions, Weaver still hadn’t provided him with the discovery documents. He says he got them only after the trial, and only after Weaver had sent him another client’s discovery by mistake.

My father testified on Rice’s behalf on the penultimate day of the trial. He had testified in other cases, and those experiences had almost always entailed long preparatory conversations with an attorney. This time was different. He’d had a single, brief conversation with Weaver by phone—a call in which she did nothing more than ask him to testify and give him a date. My father met Weaver in person for the first time in the hallway outside the courtroom. He says she gave him no instructions.

On the stand, my father articulated what he would repeat to me a decade later. From the transcript: “The amount of pain that I saw him with and the inability to stand and get onto and off the table in my office on the 20th of September makes me very dubious as to whether he could walk standing up straight, let alone run with any degree of speed, five days after I saw him.” But Weaver did not present Rice’s condition in all its dimensions—his hospital illness, his weakened muscular state. She did not explore what the stress of exertion might have done to a stapled wound if Rice had in fact started running.

And she missed something else. My father was there to testify specifically about the doctor’s-office encounter. But Weaver seems never to have obtained or reviewed Rice’s full hospital records. She certainly never introduced any such records in court. And she never called any other medical expert to testify. Had an expert witness been able to review the relevant records from the hospital—all 300 pages—he or she would have learned that Rice was dealing not only with the incision in his abdomen but also with that fractured pelvis. My father discovered references to the fractures only later, when he obtained the records on Rice’s behalf and read them for himself. The information was never introduced at the original trial, though it was certainly germane. It is impossible to say, at a remove of more than a decade, what effect these unhealed fractures would have had on the mobility of a specific individual, or how painful running might have been. Rice did tell me that, although he has learned to compensate, one of his legs is today shorter than the other.

Because Weaver had not made time to talk with my father before the trial, she was also unaware of information that might have been used to blunt a line of questioning by the prosecution. Weaver had no knowledge of my father’s conversation with Rice about painkillers, and Rice’s unwillingness to take them or to refill his prescription. So she was helpless when Eric Stryd began his cross-examination. “You find it extremely unlikely that he could actually run down the street?” the prosecutor asked. My father answered affirmatively. “Your conclusion is because of the amount of pain he would have been in?” the prosecutor went on. My father again answered affirmatively. “But you don’t know how many Percocets he may have taken on the 24th, 25th, or 26th?” Stryd asked. My father could only state the truth: “I have no way of knowing.” My father was certain that Rice had not been taking painkillers—hence the distress he saw in the examination room. But he could not say that something was completely impossible if it were not truly so. Reading the trial transcript, I realized that Weaver’s lack of knowledge and preparation had made my father’s testimony essentially a wash.

Weaver’s next witness was Deania Duncan, whose testimony was intended to support Rice’s alibi. Duncan’s son Quadifi had testified earlier in the trial that he had been at home with Rice and his grandfather all day, but his testimony had been turned against Rice. Stryd asked Quadifi why he hadn’t recorded a witness statement or said anything at all about an alibi until this very moment in court; he was able to present what should have been evidence of Weaver’s negligence—she hadn’t collected any alibi statements, despite having had almost a year and a half to do so—as evidence of Quadifi’s deceit. “Today is the first day that you’re telling anybody other than the lawyer about this?” the prosecutor asked. Quadifi assented. “He’s like your brother; you don’t want to see him get in trouble, do you?” the prosecutor continued. Quadifi assented again. “Judge, I have nothing further,” the prosecutor said.

Calling Duncan to the stand undermined Rice’s case further. In one of their two 15-minute meetings during the 14 months before his trial, Rice says he told Weaver that Duncan herself wasn’t in the house at 9:30 p.m.—the time of the shooting. He gave Weaver her name because Duncan would know everyone who had been in the house throughout the day. Although not an alibi witness herself, she’d be able to connect Weaver with everyone who could be. This distinction seems to have been lost on Weaver. As a result, when Duncan admitted under cross-examination that she hadn’t been in the house at the time of the shooting, she inadvertently left the strong impression that Rice had no alibi at all.

One piece of independently verifiable alibi evidence that could have made a difference was the location data from Rice’s cellphone. Rice had asked Weaver to retrieve the phone data, and she had promised that she would. But Weaver never did seek the data. There is nothing to be done now: After Cricket Wireless was purchased by AT&T in March 2014, records containing Rice’s data were deleted.

Speaking with me recently, Raymond Driscoll, Tyler Linder’s lawyer, recalled watching Weaver make decisions with which he disagreed—not just in terms of how those decisions might affect his own client, but how they hurt hers. Rice, Driscoll said, had what should have been strong arguments in his defense—medical incapacity, a dubious identification, no physical evidence linking him to the crime.

The strong arguments proved unavailing. On February 8, 2013, after two days of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict. Tyler Linder, represented by Driscoll, was acquitted on all counts. C. J. Rice, represented by Weaver, was found guilty on four counts of attempted murder and other associated charges. The judge ultimately banged down the gavel on a sentence of 30 to 60 years and said, “Good luck, Mr. Rice.”

In October 2016, as Rice pursued an appeal, a judge brought Weaver’s bankruptcy case to a conclusion, relieving her of her remaining debts. By then, Rice had found a new lawyer, a Philadelphia attorney named Jason Kadish, who hoped to call Weaver as a witness. After Weaver did not respond to a subpoena to appear at the evidentiary hearing, Kadish sought more information and made contact with Weaver’s daughter. He later explained to the court that Weaver was suffering a medical crisis that left her “both physically and cognitively unavailable for the purposes of today’s hearing” as well as “unavailable to provide competent testimony.” Kadish went on to note that “the prognosis is not good” and that “it does not look as if it will improve.” Weaver died in 2019.

I can remember my father saying from the time I was young, “We have a legal system, Jacob. We don’t have a justice system.” In 1971, when I was 2 years old, Philadelphia magazine ran a story that profiled my father and a number of other physicians working in poor communities in the city. It described a house call my father made, the conditions in which he worked, and the feats of organization required to bring medical care to neighborhoods that otherwise would have had none. “I wanted to work with the people,” the article quoted him as saying. “That’s why I got involved in this whole thing.”

To his patients, my father is a caring and respected physician. He is also complicated, and sometimes angry. His furrowed-brow fury has mostly been aimed from a distance—at politicians, and those who foment violence and racism, and those who display hypocrisy. My brother and I still talk about the way he yelled at the TV when a patronizing George H. W. Bush debated Geraldine Ferraro during the 1984 campaign. Under his tutelage, and at crayon-wielding age, I once drew a political cartoon of the racist Democratic mayor of Philadelphia, Frank Rizzo, consisting of his face and the words bad Rizzo bad Rizzo bad Rizzo.

For my father, C. J. Rice is not a distant cause—it is close to home. My father consults frequently with Jason Kadish, the lawyer who now represents Rice in most matters, and whom Rice’s family has found money to pay. He has marshaled medical evidence to bolster an ongoing commutation petition. He was instrumental in finding a specialist lawyer, Karl Schwartz, to handle Rice’s habeas appeal in federal court and, I suspect, has paid Schwartz himself, though he won’t say. Through my CNN colleague Van Jones, with whom I connected him, he has also helped to interest Erin Haney of the Reform Alliance in Rice’s case. Reform is a group dedicated to changing probation and parole systems around the country.

And, of course, my father and Rice write to each other. My father’s letters to Rice cover many topics. He recounts conversations he has had with Kadish. He discusses the appeals process and the efforts of Philadelphia’s district attorney, Larry Krasner, elected in 2017, to seek relief for people in circumstances similar to Rice’s. He recommends books, such as the lawyer and activist Bryan Stevenson’s memoir, Just Mercy. He brings up the Philadelphia 76ers, a subject that arouses passionate hometown feelings.

Rice told me in a recent call that as a 17-year-old, he had long hair and couldn’t grow a beard. “Now I’m going bald in the middle, and I’ve got all this facial hair.” In 2011, he was not yet 6 feet tall and weighed 160 pounds. In prison, he says he has grown a few inches and gained 70 pounds of muscle from lifting weights. Deania Duncan’s daughter Promise was a month old when Rice was arrested; he could hold her in the cup of his hands. These days, she merges phone lines for him when he calls on the weekend.

Rice earned his high-school degree while he was detained and awaiting trial; once he was sentenced, he was able to get a tutoring job, helping other inmates earn their GED. At Coal Township, he has become the experienced inmate, the jailhouse mentor who advises new detainees to get a copy of their discovery as soon as possible. He likes to read, usually nonfiction, often books about business or self-improvement. Sometimes he’ll wash his clothes by hand in the sink, just to occupy himself for 45 minutes—anything to pass the time.

Rice says that he has written Latrice Johnson at least 70 letters. In them, he has explained that he doesn’t hold her testimony against her, that he isn’t bitter. He has urged her to contact his lawyer, in the hope that something might be done on his behalf. He has never received a reply, but the letters haven’t been sent back with a return to sender label, so he believes she has been receiving them. My own luck with Johnson was no better than Rice’s. “I don’t want to relive it,” she said when I called her. “I don’t want to discuss it.” She ended the conversation. One morning in August, I stopped by her parents’ house on South 18th, looking for Johnson or anyone else who might remember the night of the shooting. The door was eventually opened by a woman who knew Johnson and may have been her mother, but who would not identify herself and whose response to every question was simply “Goodbye, sir.” A message left at another house eventually produced a return call from Johnson. “I’m the person you’re going to all of these houses looking for,” she said. “I don’t have any information for you.” She asked not to be contacted again.

Fighting to have your case overturned from a prison cell is nearly impossible. The arguments in Rice’s favor remain as strong as ever, but the nature of the case against him is an obstacle: It’s hard to call evidence into question when there was virtually no evidence to begin with. DNA wasn’t a factor. Impropriety by the police didn’t play a role.

The passage of time can have a flattening effect—perspective can get lost and key facts forgotten. Murray Cohen, the surgeon who operated on Rice, never testified at the original trial. During Rice’s appeal, in 2019, he was called to testify for the commonwealth, and against Rice. Cohen had not evaluated Rice’s condition, weeks after the operation, as my father had; after the hospital stay, Cohen and Rice came face-to-face again only in court during that appeal, seven years later. Cohen did not believe that running would have made staples or sutures come loose—“not my staples and not my suture.” He described the surgery and what he thought would be Rice’s condition on the day of the shooting: “It was a laparotomy with no internal injury,” Cohen stated, meaning that the bullet had not damaged the intestines. “He was 21, 22 days post-op. I didn’t observe the patient that day, but a typical 17-year-old would be able to run.” But Rice was not a typical 17-year-old; among other things, a bullet had fractured his pelvis. According to the Hospital for Special Surgery, patients with a fractured pelvis may require six to 12 weeks for full restoration of function. (Cohen could not be reached for comment.)

What of the argument that Rice was represented by ineffective counsel? It’s a powerful one, at least in the eyes of an ordinary person looking at the facts. That doesn’t mean it carries any weight in a legal system set up in so many ways to protect itself.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees defendants the right to counsel. In a 1984 case, Strickland v. Washington, the U.S. Supreme Court took up the question of just how bad lawyers need to be before their performance proves constitutionally defective. Writing for the majority, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor established a two-part test: A lawyer’s performance falls short of the Sixth Amendment’s right to counsel if (a) it is deficient and (b) that deficiency prejudices the defense, depriving the defendant of a fair trial. The opinion went on to define a deficient counsel as one who “made errors so serious that counsel was not functioning as the ‘counsel’ guaranteed the defendant by the Sixth Amendment”—a definition that is not only vague but circular. The inadequacy of the standard has allowed a patchwork of different rules to proliferate across the country. A lawyer can sleep during part of a client’s cross-examination, or be arrested for drunk driving on the way to court, or be mentally unstable, or have been disbarred midway through a trial without sinking to the level of constitutionally defective performance—all of these instances have been adjudicated in various jurisdictions. This spring, the Supreme Court further restricted the right to claim ineffective counsel as the basis for an appeal. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, writing in dissent, declared that the decision “reduces to rubble” a defendant’s Sixth Amendment guarantee. Most of the largest counties across the country have a system like Philadelphia’s, where court-appointed attorneys such as Sandjai Weaver are among the only options for defendants like C. J. Rice.

Justice Thurgood Marshall, the sole dissenter in the Strickland case, faulted the ruling for a “debilitating ambiguity” that compelled judges to rely on “intuitions” about what constitutes ineffective counsel. Under Pennsylvania’s Post Conviction Relief Act, the person whose intuition matters is the original trial judge—this is the person who first considers an appeal. When the matter came before him, Denis Cohen, the judge who had wished Rice good luck, found that Weaver was not deficient counsel. (Through a spokesperson for the Philadelphia courts, Cohen declined to comment, referring to his opinions in Rice’s case.) Rice appealed Cohen’s judgment to the Pennsylvania Superior Court. He was again disappointed: The Superior Court affirmed Cohen’s ruling. Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court would not take up the case.

For a while, Rice and his allies had looked hopefully to the creation of a much-publicized Conviction Integrity Unit—one of Larry Krasner’s first acts as D.A. The job of the CIU is to review past cases, looking for those in which convictions were unwarranted or sentences were too harsh. In 2021, the CIU issued a report that made reference to “a vicious system that lacked transparency and accountability” and highlighted the unit’s successes. But success in this context has meant the exoneration of only 25 individuals out of more than 800 reviewed cases as of August 2022. As fears about crime heighten in cities across the country, efforts such as the CIU face ferocious opposition from police associations, and from some courts and politicians. D.A.s find themselves treading carefully, mindful of cautionary examples like that of Chesa Boudin, the San Francisco prosecutor who was turned out of office in June. Virtually all of the CIU’s exonerations have involved open-and-shut cases of police or prosecutorial misconduct—that’s the threshold that needs to be met. The greater damage done by the “vicious system” functioning as usual will apparently not get a second look.

When I began reporting this story, in 2020, the Conviction Integrity Unit had some 1,400 cases pending review. In April, the D.A.’s office told me that Rice’s case was no longer being considered. In an emailed statement, a spokesperson said that the CIU had decided that there was an “insufficient legal and factual basis to warrant the Commonwealth intervening to vacate his conviction.” The spokesperson emphasized that the decision was “not confirmation that his conviction was sound.”

Rice’s remaining options are few. Barring some new development, he will have to serve at least 20 and as many as 50 more years in prison. A federal habeas petition will soon be filed, but the record in cases like this one is not grounds for optimism. A petition to the state Board of Pardons is being prepared on Rice’s behalf. A commutation or pardon is in the hands of the board’s five members. They include the lieutenant governor, John Fetterman, a candidate for the Senate this year, and the attorney general, Josh Shapiro, a candidate for governor.

In September 2011, the month C. J. Rice was arrested, the state legislature of Pennsylvania released its “Report of the Advisory Committee on Wrongful Convictions.” The 316-page document ticked off many failures, including lack of state funding for the defense of people without means—Pennsylvania provides none to public defenders at all—as well as the unreliability of eyewitness testimony and suspect lineups. It offered a long list of recommendations, almost none of which have been adopted.

The reality is that Commonwealth v. Charles J. Rice represents nothing out of the ordinary. The Conviction Integrity Unit’s caseload captures the situation in a single city, but the same reality exists everywhere. Reforms, even if enacted, would scarcely touch the deeper dysfunction—not just of the criminal-justice system but of neighborhoods and schools. In too many cases, “reform” simply allows dysfunction to remain functional. Rice’s story has produced no bumper stickers or T-shirts or movies. There is no corrupt cop or evil prosecutor. There is only doubtful evidence, deficient counsel, and the relentless grind of the criminal-justice system itself. Rice’s story is meaningful precisely because it is not unusual. Change the details, and it is the story of tens of thousands of poor defendants and the accumulation of large and small injustices that define their lives.

The only unusual thing about Rice’s story is the quirk of fate—his doctor is the father of a journalist—that has gained it any attention at all. To examine his case is to watch a conveyor belt leading in a single direction, with escape routes slamming shut the moment each is glimpsed: a public defender rather than a court-appointed attorney; a routine check of cellphone data; a timely notice of alibi; the right questions put to a dubious eyewitness; a Kloiber instruction by the judge; a request for hospital records; the testimony of an independent medical expert; a defense counsel familiar with the crime scene; a Sixth Amendment that is taken seriously.

Let me state the obvious, in personal terms: With evidence as meager as that against Rice, no prosecutor in the country would even have charged me, a white man with resources. If it had—and if I’d had legal representation worthy of the name—no jury would have brought a conviction.

Andrew Aoyama contributed reporting. This article appears in the November 2022 print edition with the headline “‘Good Luck, Mr. Rice.’”