Beth Nguyen’s essay “Apparent,” on her absent mother and piecing together a fractured past, appears in our Spring issue.

I have no pictures of myself as a baby. I was born in Saigon during a war, and was eight months old when my family became refugees; my memories begin in a worn-down house in a deeply conservative town in Michigan, where we were resettled.

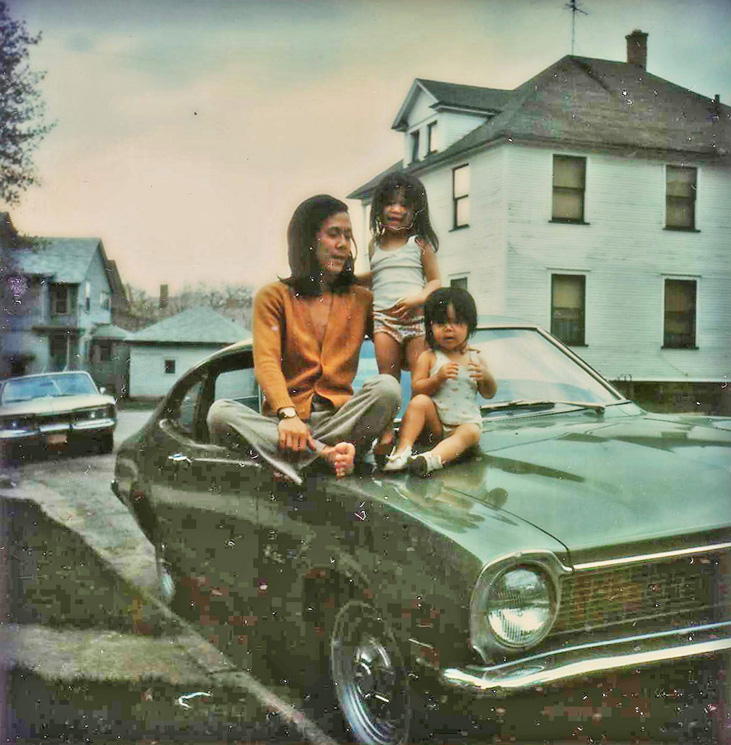

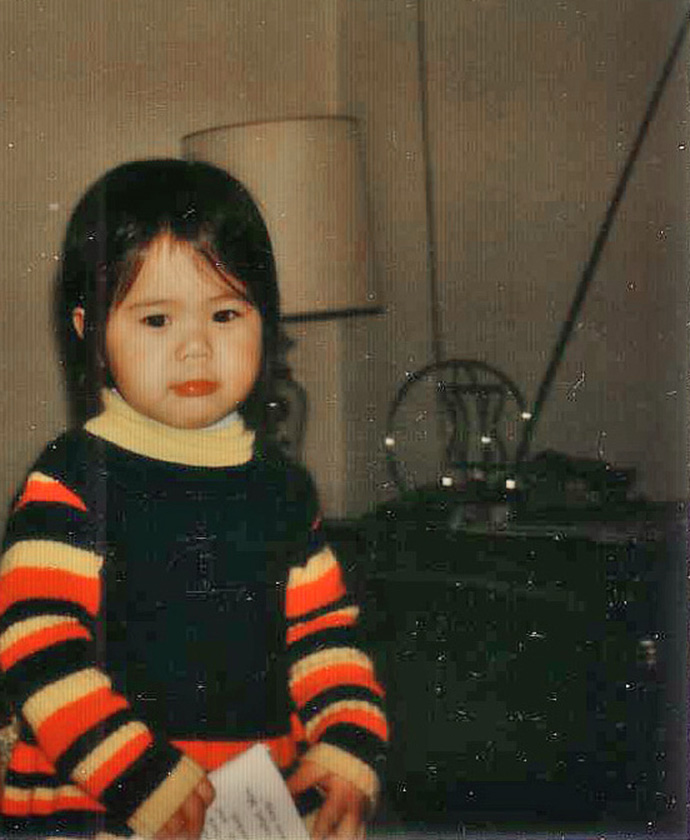

Photographs were expensive then, so we had few of them. The Polaroid colors are muted and mottled, an expression of what it felt like to grow up in a Vietnamese refugee family surrounded by whiteness. It has taken my entire life to understand the beginnings of this awareness. It began with watching my father go to work at a feather factory and come home with down in his hair. My uncles, who shared the house with us, worked different shifts at different factories. They saved money to buy records. My grandmother Noi took care of me and my sister. She knitted us ponchos out of marled yarn, let us wear fuzzy pink slippers into the snow.

I didn’t know what it meant to be a refugee, but I knew we were different because on TV shows everyone else spoke another language. My sister and I learned English this way. I don’t remember wondering where my mother was or realizing she was still in Viet Nam. I didn’t even know what a mother was until I was told. My grandmother would give whole apples and pears to my sister and me, knowing that we would save them. We were always waiting for someone to come home.

All family pictures create a chronology. But I realize only now that the pictures we took and kept were a space just for us. White people determined so much about our lives—jobs, schools, language—but not in these photos. In these images we seem to be in our own world, alone together. It’s such a short time. By the last picture, it’s over.

Why are my father, my sister, and I hanging out on this car? Whose car is it? (It’s not ours.) Why are we dressed like this? Where did my father get that fantastic cardigan? This is my favorite photo because it is unfamiliar to me every time I see it, yet the sky looks the way I remember my childhood. I am two or three years old here, too young to remember this scene itself. I want to believe there was joy and relaxation—my father, barefoot as he loved to be—even though that’s not what I associate with growing up.

This is what my life was like until I left for college: a book in one hand and a television nearby. I didn’t know it then, but my obsession with words was a method of survival. I read every bit of English I could find: instruction manuals, newspapers, the backs of cereal boxes, library books. I studied the diction of actresses on shows like The Love Boat and Fantasy Island. I cared more about words than about what I wore, but I loved this dress and I still do. This is probably the cutest picture I’ll ever take.

My grandmother Noi always wore an áo dài whenever we left the house. It wasn’t to be fancy or to call attention to herself; it was to be Vietnamese. Inside the house, she wore flowing polyester pants and a light tunic, adding a hand-knit cardigan in the colder months. She made all of her clothes herself. This was how I knew her, from my first moments of consciousness to the day she died at age eighty-seven. She would take us to parks and watch TV with us but never spoke to us in English. When white kids made fun of her, she understood the racism but often laughed at it, a light laugh that conveyed dismissal. She’s been gone for more than ten years now and I am still in awe of her.

In truth, my sister was more cheerful. I looked to her to figure out what I should feel instead of what I was feeling. She was the one who said we should save the fruit that our grandmother gave us. It was a treat just to hold the apples and pears. We didn’t even know how to eat them whole. We thought fruit had to be sliced before it could be eaten; it had to be set forth on little plates, because that’s what our grandmother did. I think I was twelve before I bit into a whole apple.

Fast forward to age eight, maybe nine? That’s the year I’m obsessed with Pez dispensers, the neatness of the form. I have nail polish on because my sister makes me, but really, I hate it. Still do. I’m watching this face and body painting but I won’t participate. I can’t bear the feel of it, don’t want someone else drawing on any part of me. I am at this age already so much who I will become.

Read Beth Nguyen’s essay in our Spring issue.

Beth Nguyen is the author of the memoir Stealing Buddha’s Dinner and the novels Short Girls and Pioneer Girl. She is the recipient of an American Book Award, and a PEN/Jerard Award, among other honors. Her work has appeared in numerous anthologies and publications including the New York Times, Literary Hub, and The Paris Review. She is at work on a series of linked essays about post-refugee life, titled Owner of a Lonely Heart.