Here’s where detective work pays off, as we begin to trace more frequent reuses and modifications of old material (sometimes from the same studios holding the original copyrights, sometimes not) among the steady output of aerial cartoons produced during the early 1930’s. While there continues to be variety in the manner in which planes traveled up or down, some animators found ways of back-tracking to previous ideas for reuse (in at least two instances discussed at length below, of necessity to save a project that would otherwise have been scrapped). Hop aboard for another overview to elevate the mind and tickle the funny bone like a feather.

I begin with sincere apologies for a chronological mixup, placing out of sequence discussion of our first cartoon, Plane Dumb (Van Buren/RKO, Tom and Jerry, 6/25/32 – John Foster/George Rufle, dir.). Technically, it is a series entry that was not supposed to exist, as its footage was intended for another purpose entirely. It was conceived under the title, “All Wet”. as an animated vehicle for a Vaudeville comedy team of Fluornoy E. Miller and Aubrey Lyles, whose voices appear on the soundtrack The team were actual black comedians, who rose to fame in the revue, “Shuffle Along” in 1921, and also made commercial recordings of comedy routines for both Okeh and Banner records. Titling prepared for such original release still exists. However, Lyles was suffering from tuberculosis, to which he succumbed later in the year, and rumors are that he may never have completed his recording of voice work for the film’s original frameworking. The concept of releasing the nearly completed film in its original format had to be scrapped, but the studio realized that their visual concept of the characters was not that dissimilar to the dimensions of their new stars Tom and Jerry – so the idea was hatched to save the footage by having Tom and Jerry “blacken up” to transform them into the Miller and Lyles characters, allowing the existing footage to be recycled into a cobbled storyline. The result is strange to say the least, inconsistent with the personas of the duo in their other films, and has to be seen to be believed.

I begin with sincere apologies for a chronological mixup, placing out of sequence discussion of our first cartoon, Plane Dumb (Van Buren/RKO, Tom and Jerry, 6/25/32 – John Foster/George Rufle, dir.). Technically, it is a series entry that was not supposed to exist, as its footage was intended for another purpose entirely. It was conceived under the title, “All Wet”. as an animated vehicle for a Vaudeville comedy team of Fluornoy E. Miller and Aubrey Lyles, whose voices appear on the soundtrack The team were actual black comedians, who rose to fame in the revue, “Shuffle Along” in 1921, and also made commercial recordings of comedy routines for both Okeh and Banner records. Titling prepared for such original release still exists. However, Lyles was suffering from tuberculosis, to which he succumbed later in the year, and rumors are that he may never have completed his recording of voice work for the film’s original frameworking. The concept of releasing the nearly completed film in its original format had to be scrapped, but the studio realized that their visual concept of the characters was not that dissimilar to the dimensions of their new stars Tom and Jerry – so the idea was hatched to save the footage by having Tom and Jerry “blacken up” to transform them into the Miller and Lyles characters, allowing the existing footage to be recycled into a cobbled storyline. The result is strange to say the least, inconsistent with the personas of the duo in their other films, and has to be seen to be believed.

To set the film in Africa, the cartoon’s titles are oddly superimposed over a live-action image of one of Africa’s picturesque waterfalls (I believe Victoria). Tom and Jerry begin the film in the last stages of a non-stop flight to Africa, by which pilot Tom claims they will become heroes. The normally adventurous Jerry is unusually reluctant, claiming that they won’t be safe in Africa. Tom suggests using black paint to disguise themselves and blend in with the locals. Once the paint is applied, the footage switches to the Miller and Lyles cartoon, all in stereotypical dialogue. The plane develops engine trouble, and dives into the ocean, where it comes up barely floating, with only its top wing above water. Jerry (Lyles) wonders at what speed they’re drifting, and Tom (Miller) explains knots by counting passing waves, which crash together and appear to tie themselves in visual knots with each other. An octopus climbs upon the wing with them, and grabs the duo with its many arms. Tom disapproves when the beast kisses him, socking the creature in the chops. The octopus retaliates by spinning like a pinwheel, administering a multi-tentacle paddling upon Tom’s rear end, then departing. Next, the two find themselves giggling without knowing why, only to find their toes are being tickled by passing shark fins in the water. “Will they eat you?” asks Jerry. “If they don’t, they’ll sure mess you up plenty”, replies Tom A swordfish appears to slice their plane wing in two, forcing the duo to abandon their floatation device and dive toward the water. They never quite make it, as a rotating ring of sharks appears under their feet, having the effect of forming a rotating treadmill upon which the boys run, as if upon the outside of a hamster wheel. “We is running, ain’t we?”, says Tom. “But we ain’t gettin’ noplace”, responds Jerry. “Something fishy about this”, observes Tom. Suddenly, the boys appear to be rising, and believe they are being picked up by a submarine. Instead, it is the back of a whale, Pushing Jerry down upon the whale’s blowhole, Tom proposes that this should “smother him”. Instead, the two are launched by a spout of water onto the African shore. A sequence in a cave includes some late dialogue added by Miller for the rewrite, in which he actually refers to his partner as “Jerry”, while Lyles, of course unavailable, never refers in his dialogue to “Tom”. Another sign of a grafted-on shot os a reuse of old animation of a black skeleton quartet, left over from Tom and Jerry’s first film, “Wot a Night”. The final scene is also an add-on, having the boys chased by headhunters, in the course of which they remove their makeup, just to really prove to the audience it was them after all. It is easy to observe that sound recording for the film is exceptionally poor, with lines delivered with unusually low volume and lack of clarity, and very choppy splicing between lines where “pops” can be easily heard when lines are spliced together. Possibly, the existing tracks were not envisioned as the final takes, and would have been re-recorded but for Lyles’ health problems. The final cut seems hastily thrown together, simply making use of whatever was available.

To set the film in Africa, the cartoon’s titles are oddly superimposed over a live-action image of one of Africa’s picturesque waterfalls (I believe Victoria). Tom and Jerry begin the film in the last stages of a non-stop flight to Africa, by which pilot Tom claims they will become heroes. The normally adventurous Jerry is unusually reluctant, claiming that they won’t be safe in Africa. Tom suggests using black paint to disguise themselves and blend in with the locals. Once the paint is applied, the footage switches to the Miller and Lyles cartoon, all in stereotypical dialogue. The plane develops engine trouble, and dives into the ocean, where it comes up barely floating, with only its top wing above water. Jerry (Lyles) wonders at what speed they’re drifting, and Tom (Miller) explains knots by counting passing waves, which crash together and appear to tie themselves in visual knots with each other. An octopus climbs upon the wing with them, and grabs the duo with its many arms. Tom disapproves when the beast kisses him, socking the creature in the chops. The octopus retaliates by spinning like a pinwheel, administering a multi-tentacle paddling upon Tom’s rear end, then departing. Next, the two find themselves giggling without knowing why, only to find their toes are being tickled by passing shark fins in the water. “Will they eat you?” asks Jerry. “If they don’t, they’ll sure mess you up plenty”, replies Tom A swordfish appears to slice their plane wing in two, forcing the duo to abandon their floatation device and dive toward the water. They never quite make it, as a rotating ring of sharks appears under their feet, having the effect of forming a rotating treadmill upon which the boys run, as if upon the outside of a hamster wheel. “We is running, ain’t we?”, says Tom. “But we ain’t gettin’ noplace”, responds Jerry. “Something fishy about this”, observes Tom. Suddenly, the boys appear to be rising, and believe they are being picked up by a submarine. Instead, it is the back of a whale, Pushing Jerry down upon the whale’s blowhole, Tom proposes that this should “smother him”. Instead, the two are launched by a spout of water onto the African shore. A sequence in a cave includes some late dialogue added by Miller for the rewrite, in which he actually refers to his partner as “Jerry”, while Lyles, of course unavailable, never refers in his dialogue to “Tom”. Another sign of a grafted-on shot os a reuse of old animation of a black skeleton quartet, left over from Tom and Jerry’s first film, “Wot a Night”. The final scene is also an add-on, having the boys chased by headhunters, in the course of which they remove their makeup, just to really prove to the audience it was them after all. It is easy to observe that sound recording for the film is exceptionally poor, with lines delivered with unusually low volume and lack of clarity, and very choppy splicing between lines where “pops” can be easily heard when lines are spliced together. Possibly, the existing tracks were not envisioned as the final takes, and would have been re-recorded but for Lyles’ health problems. The final cut seems hastily thrown together, simply making use of whatever was available.

Ireland or Bust (Terrytoons/Educational, 12/25/32) – Paul Terry seems to have stood alone among animators in possessing interest in Polar flights and aerial trips to Ireland. These feats had already been accomplished in the late 1920’s, but Terry continued to produce cartoons about them long afterwards. In this one, his aviators are an unnamed cat and mouse duo. Their plane is a twin engine monoplane dubbed “Shamrock”. They bow to what appears to be the same crowd as in “Lindy’s Cat”, then each spin a prop – getting sucked into the propellers, and thrown out behind the plane, leaving them to chase the craft down the runway before it takes off from the cliffs. Or at least tries to. Instead of rising, the plane quickly takes a nose dive into the ocean, flounders around in the water, and washes up on the beach. The reason? An elephant, and half the menagerie of the zoo, have hidden in the cabin as stowaways. After chasing away the intruders, the plane is airworthy again. The plane heads out over New York harbor, flying low and severing in two the masts and smokestacks of an ocean liner. With several animals watching from atop her shoulders and the creases of her gown, an unusually rotund Statue of Liberty (who looks like she’s gained pounds from listening to Kate Smith) dances a farewell dance to the adventurers. Without so much as a dissolve or a map view, the aviators are suddenly over the Arctic, with walruses, seals, and bears bidding them a greeting below. One group of animals hops on the shadow of the plane and rides it (a gag later remembered in the 40’s in Super Mouse Rides Again), until the shadow passes over a cliff edge, dumping the passengers into the icy water below.

Ireland or Bust (Terrytoons/Educational, 12/25/32) – Paul Terry seems to have stood alone among animators in possessing interest in Polar flights and aerial trips to Ireland. These feats had already been accomplished in the late 1920’s, but Terry continued to produce cartoons about them long afterwards. In this one, his aviators are an unnamed cat and mouse duo. Their plane is a twin engine monoplane dubbed “Shamrock”. They bow to what appears to be the same crowd as in “Lindy’s Cat”, then each spin a prop – getting sucked into the propellers, and thrown out behind the plane, leaving them to chase the craft down the runway before it takes off from the cliffs. Or at least tries to. Instead of rising, the plane quickly takes a nose dive into the ocean, flounders around in the water, and washes up on the beach. The reason? An elephant, and half the menagerie of the zoo, have hidden in the cabin as stowaways. After chasing away the intruders, the plane is airworthy again. The plane heads out over New York harbor, flying low and severing in two the masts and smokestacks of an ocean liner. With several animals watching from atop her shoulders and the creases of her gown, an unusually rotund Statue of Liberty (who looks like she’s gained pounds from listening to Kate Smith) dances a farewell dance to the adventurers. Without so much as a dissolve or a map view, the aviators are suddenly over the Arctic, with walruses, seals, and bears bidding them a greeting below. One group of animals hops on the shadow of the plane and rides it (a gag later remembered in the 40’s in Super Mouse Rides Again), until the shadow passes over a cliff edge, dumping the passengers into the icy water below.

A wonderful almost three-dimensional moving background scene depicts a tracking shot from point of view a short distance behind the plane, as the craft passes over icy waters full of protruding icebergs passing the camera. The plane drills nose first into the tip of a tall iceberg, and comes out the other side wearing a thick blanket of snow. Inside the cockpit, the cat notices the altimeter falling, and sends the mouse outside with a snow shovel. The mouse clears away most of the snow, except for a large lump near the tail, which turns out to be a snow-covered polar bear who seems to have eyes for the mouse, sidling up to him with a romantic stare. The mouse pushes the bear into an icy slide off the end of the tail, bit almost succumbs to the same slide himself from the forceful blow of the propellers. He grabs hold of the top of the forward windshield, through which the cat is attempting to squint to get his bearings, and without planning it helps the cat by suddenly dangling from the windshield frame by his tail, swinging back and forth to become a living windshield wiper, much to the cat’s delight. Suddenly the flight is over, as a bolt of lightning blasts the aircraft apart, and the two aviators float to earth as their suspender pants inflate as parachutes. But the boys have just made it, as they float down to a lighthouse on the Irish coast. They land atop the beacon, and the beam of light suddenly contracts from straight to jagged, forming the shape of a staircase for them to descend to the ground. However, once they have stepped upon it, the beam straightens out again, causing them to touch land much faster with a quick tumbling slide.

A wonderful almost three-dimensional moving background scene depicts a tracking shot from point of view a short distance behind the plane, as the craft passes over icy waters full of protruding icebergs passing the camera. The plane drills nose first into the tip of a tall iceberg, and comes out the other side wearing a thick blanket of snow. Inside the cockpit, the cat notices the altimeter falling, and sends the mouse outside with a snow shovel. The mouse clears away most of the snow, except for a large lump near the tail, which turns out to be a snow-covered polar bear who seems to have eyes for the mouse, sidling up to him with a romantic stare. The mouse pushes the bear into an icy slide off the end of the tail, bit almost succumbs to the same slide himself from the forceful blow of the propellers. He grabs hold of the top of the forward windshield, through which the cat is attempting to squint to get his bearings, and without planning it helps the cat by suddenly dangling from the windshield frame by his tail, swinging back and forth to become a living windshield wiper, much to the cat’s delight. Suddenly the flight is over, as a bolt of lightning blasts the aircraft apart, and the two aviators float to earth as their suspender pants inflate as parachutes. But the boys have just made it, as they float down to a lighthouse on the Irish coast. They land atop the beacon, and the beam of light suddenly contracts from straight to jagged, forming the shape of a staircase for them to descend to the ground. However, once they have stepped upon it, the beam straightens out again, causing them to touch land much faster with a quick tumbling slide.

But wait! The cartoon’s barely half over, although its aerial references abruptly end at this point. The remainder of the film consists of utter nonsense in an old Irish castle, with a character who rides a broom like a witch, but has a buzzard’s face (presumably a banshee). With no motivation provided, this creature has a sweet young mouse tied to a log heading for a buzzsaw, in typical melodramatic fashion. The boys try to track down the source of the screams by following a mysterious green line on the castle floor, encounter a goat guard and a room full of ghosts, and finally sail away with the freed damsel. How easy it was for ‘30’s characters to lose their way entirely – and after all the time and effort it took just to get there!

But wait! The cartoon’s barely half over, although its aerial references abruptly end at this point. The remainder of the film consists of utter nonsense in an old Irish castle, with a character who rides a broom like a witch, but has a buzzard’s face (presumably a banshee). With no motivation provided, this creature has a sweet young mouse tied to a log heading for a buzzsaw, in typical melodramatic fashion. The boys try to track down the source of the screams by following a mysterious green line on the castle floor, encounter a goat guard and a room full of ghosts, and finally sail away with the freed damsel. How easy it was for ‘30’s characters to lose their way entirely – and after all the time and effort it took just to get there!

The Beer Parade (Charles Mintz/Columbia, Scrappy, 3/8/33, Dick Heumor, dir.), finds Scrappy and Oopie contributing to the delinquency of their elders, by acting as junior bartenders to a community of inebriated elves, who just can’t get enough of that home brew. Until old man Prohibition rears his ugly head, taking an axe to all of their precious ale barrels. Courageous Oopie sets out to see this wrong avenged, and Scrappy too joins the battle, as they and the elves wage a mammoth war against the dried-up specter. The battle transforms into an aerial conflict, as Oopie and an elf develop a new means of powered flight. Uprooting a long-stemmed daisy, Oopie seats himself on the stem as if riding a witch’s broom, while the elf blows into the bottom of the stem, twirling the flower’s petals like a pinwheel to achieve propeller propulsion. A squadron of elves follow on such devices, and, flying in a wedge formation, they bombard Prohibition with empty beer glasses! Needless to say, Prohibition is ultimately vanquished, and the boys are back to setting up another round, complete with salted pretzels and free lunch!

The Air Race (Ub Iwerks, Willie Whopper, unreleased 1933) remains a mystery among Iwerks productions. Arguably one of the finest installments in the Willie series, this episode, filmed with full MGM credits and intended as the introduction of the series, was for unknown reasons scrapped and rejected by MGM, never to be publicly screened. There is no logical reason why. The format of the cartoon is identical to subsequent chapters which went into public release, and the design of the character essentially the same as used in subsequent issued cartoons. While there is at least one gag which is decidedly pre-code, the cartoon is otherwise largely lacking in off-color or blue humor, so that it would not seem to have been capable of offending MGM executives. In fact, the one over-the-top gag actually makes an appearance again in an issued cartoon discussed below, so it certainly couldn’t have been the cause of the cartoon’s rejection. To make things more confusing, the subsequent issued episode discussed below is a partial reworking of the same script, but inferior in quality – so why was the inferior cartoon deemed acceptable, while the elaborate premiere was left to languish in the vaults? Some have speculated that a celebrity caricature of pioneer female aviator Amelia Earhart might have had something to do with MGM’s decision – but the studio had no problem with having Willie meet Babe Ruth in the substituted series premiere, “Play Ball”, so again the theory does not hold water. We may never know for sure why this well-made cartoon would ever arouse disfavor in any viewer’s eyes.

The Air Race (Ub Iwerks, Willie Whopper, unreleased 1933) remains a mystery among Iwerks productions. Arguably one of the finest installments in the Willie series, this episode, filmed with full MGM credits and intended as the introduction of the series, was for unknown reasons scrapped and rejected by MGM, never to be publicly screened. There is no logical reason why. The format of the cartoon is identical to subsequent chapters which went into public release, and the design of the character essentially the same as used in subsequent issued cartoons. While there is at least one gag which is decidedly pre-code, the cartoon is otherwise largely lacking in off-color or blue humor, so that it would not seem to have been capable of offending MGM executives. In fact, the one over-the-top gag actually makes an appearance again in an issued cartoon discussed below, so it certainly couldn’t have been the cause of the cartoon’s rejection. To make things more confusing, the subsequent issued episode discussed below is a partial reworking of the same script, but inferior in quality – so why was the inferior cartoon deemed acceptable, while the elaborate premiere was left to languish in the vaults? Some have speculated that a celebrity caricature of pioneer female aviator Amelia Earhart might have had something to do with MGM’s decision – but the studio had no problem with having Willie meet Babe Ruth in the substituted series premiere, “Play Ball”, so again the theory does not hold water. We may never know for sure why this well-made cartoon would ever arouse disfavor in any viewer’s eyes.

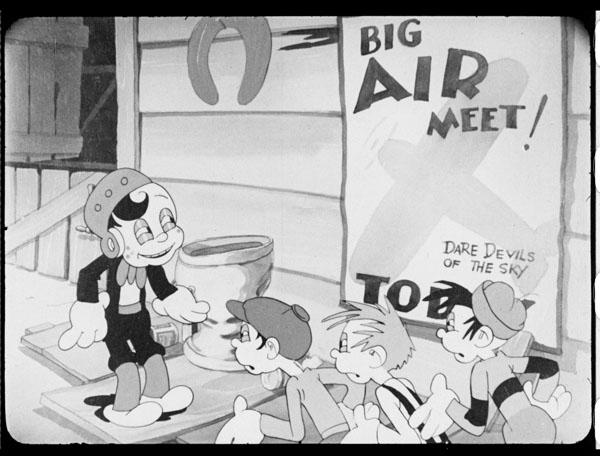

As with most of Willie’s tales, an occurrence in the real world prompts Willie to begin boasting about mythical past exploits of derring-do. Here, the impetus is a poster on a barn wall advertising an upcoming air meet. Willie claims that such an event is nothing, as he once competed in the National Air Races. The camera flashes back by way of a fade to black, the black being revealed as the shadowy underside of the wing of a plane about to make a landing at the airstrip of a location known as Corn Field. Iwerks brings with him memories of Oswald Rabbit’s The Ocean Hop, as an establishing shot of planes lined up and warming up for takeoff bears striking resemlance to a similar scene in the Oswald film. We first see several of Willie’s competitors and their strange inventions. One plane utilizes a rotary motor system, but with bubbling coffee pots placed in a circle where the cylinders should be, and is named the Perkle 8. A second entry looks like it stepped straight out of a famous newsreel compilation of failed flying machines (which would appear in Robert Youngston shorts, in the credits of Super Chicken, and in one of its longest versions as the intro to Vincent Price’s Master of the World for American International). It consists of a bicycle, the pedals of which are attached to a set of flapping wings mounted above the passenger seat. Another entry is a full size steam locomotive, with wings mounted on the sides, a nose prop extending from the front of the boiler, and an autogyro prop extending out of the smokestack. The villain (in a plane referred to on the entry board as “The Buzzard”) flies a long black streamlined job, containing a row of about 21 inline cylinders under the hood, tuned to perfection with a tuning fork. (The same engine seems to have made its way under the hood of the car of Boris Karoff in “Porky’s Road Race”, though Iwerks had no known connection with such film.) What about Willie? He is flying a pipsqueak little plane whose sole source of power is an outboard motor lifted from someone’s old motorboat. In a shot again suspiciously similar to Oswald’s “The Ocean Hop”, the villain spots Willie’s plane, inspects it, and breaks into uproarious laughter as did Putrid Pete. But Iwerks adds a nice touch here. The villain, who is at first seen with a black beard, gets the prop of Willie’s plane spinning, then lifts up Willie and the plane with one hand, and uses the propeller as an electric shaver to neatly trim his beard off for a clean-shave. Reverting again to the Oswald gags, the plane retaliates by blowing a puff of sooty smoke in the villain’s face, blackening him up. He states to the audience in a Southern dialect, “Fan my brow!”

As with most of Willie’s tales, an occurrence in the real world prompts Willie to begin boasting about mythical past exploits of derring-do. Here, the impetus is a poster on a barn wall advertising an upcoming air meet. Willie claims that such an event is nothing, as he once competed in the National Air Races. The camera flashes back by way of a fade to black, the black being revealed as the shadowy underside of the wing of a plane about to make a landing at the airstrip of a location known as Corn Field. Iwerks brings with him memories of Oswald Rabbit’s The Ocean Hop, as an establishing shot of planes lined up and warming up for takeoff bears striking resemlance to a similar scene in the Oswald film. We first see several of Willie’s competitors and their strange inventions. One plane utilizes a rotary motor system, but with bubbling coffee pots placed in a circle where the cylinders should be, and is named the Perkle 8. A second entry looks like it stepped straight out of a famous newsreel compilation of failed flying machines (which would appear in Robert Youngston shorts, in the credits of Super Chicken, and in one of its longest versions as the intro to Vincent Price’s Master of the World for American International). It consists of a bicycle, the pedals of which are attached to a set of flapping wings mounted above the passenger seat. Another entry is a full size steam locomotive, with wings mounted on the sides, a nose prop extending from the front of the boiler, and an autogyro prop extending out of the smokestack. The villain (in a plane referred to on the entry board as “The Buzzard”) flies a long black streamlined job, containing a row of about 21 inline cylinders under the hood, tuned to perfection with a tuning fork. (The same engine seems to have made its way under the hood of the car of Boris Karoff in “Porky’s Road Race”, though Iwerks had no known connection with such film.) What about Willie? He is flying a pipsqueak little plane whose sole source of power is an outboard motor lifted from someone’s old motorboat. In a shot again suspiciously similar to Oswald’s “The Ocean Hop”, the villain spots Willie’s plane, inspects it, and breaks into uproarious laughter as did Putrid Pete. But Iwerks adds a nice touch here. The villain, who is at first seen with a black beard, gets the prop of Willie’s plane spinning, then lifts up Willie and the plane with one hand, and uses the propeller as an electric shaver to neatly trim his beard off for a clean-shave. Reverting again to the Oswald gags, the plane retaliates by blowing a puff of sooty smoke in the villain’s face, blackening him up. He states to the audience in a Southern dialect, “Fan my brow!”

Time for the race to begin. While Willie is pleasantly distracted by a thrown kiss from celebrity trophy presenter Amelia Earhart, the villain repeats Putrid Pete’s tactic of sticking chewing gum under the wheel of Willie’s plane. The judge’s firing gun is sounded unusually – as a balloon inflates out of the barrel, with the judge popping it with his lighted cigar to achieve the required “boom”. The racers are off – except for Willie, whose engine finally breaks loose from the plane’s nose, does a U-turn, and pushes upon the plane’s tail to break it free from the gum. As the rest of the racers forge ahead, they pass a cloud on which rests the pearly gates of heaven – and gatekeeper St. Peter thumbing for a ride like a hitchhiker. One plane passes him, and in a manner much less than heavenly, Peter breaks all codes of good taste by extending his middle index finger at the plane instead of his thumb! The villain sets about his dirty work, barreling into the tails of several opponents to knock them out of the skies. One pilot parachutes to safety, while another has packed a knap sack full of old dishes instead of a parachute by mistake. As he plummets past St. Peter’s cloud, Peter adopts the mannerisms of Mae West, and invites the doomed pilot to “Come up and see me sometime”.

Time for the race to begin. While Willie is pleasantly distracted by a thrown kiss from celebrity trophy presenter Amelia Earhart, the villain repeats Putrid Pete’s tactic of sticking chewing gum under the wheel of Willie’s plane. The judge’s firing gun is sounded unusually – as a balloon inflates out of the barrel, with the judge popping it with his lighted cigar to achieve the required “boom”. The racers are off – except for Willie, whose engine finally breaks loose from the plane’s nose, does a U-turn, and pushes upon the plane’s tail to break it free from the gum. As the rest of the racers forge ahead, they pass a cloud on which rests the pearly gates of heaven – and gatekeeper St. Peter thumbing for a ride like a hitchhiker. One plane passes him, and in a manner much less than heavenly, Peter breaks all codes of good taste by extending his middle index finger at the plane instead of his thumb! The villain sets about his dirty work, barreling into the tails of several opponents to knock them out of the skies. One pilot parachutes to safety, while another has packed a knap sack full of old dishes instead of a parachute by mistake. As he plummets past St. Peter’s cloud, Peter adopts the mannerisms of Mae West, and invites the doomed pilot to “Come up and see me sometime”.

Next comes a gag which gives some cause for speculation. Play Ball, the official premiere of the Willie Whopper series, was released in September, 1933, such that it is a safe bet that “Air Race” was produced earlier in the year. But how early? The cause for concern is a gag which appears nearly simultaneously in Mickey Mouse’s The Mail Pilot (discussed below) and in this cartoon – as Willie gets his propeller trimmed off by the villain, but regains a prop by crashing nose-first into the blades of a farm windmill. Former UCLA animation professor Dan McLaughlin speculated as to whether this and several more “coincidences” within the ensuing year gave indication that there was a spy somewhere in the ranks of either the Disney or Iwerks studios reporting to the other, allowing for the pirating of ideas even before films received official release. There might be some credence to this theory, given another “Mail Pilot” gag that is lifted into the Whopper reworking discussed below, and the surprising coincidence the following year of both studios being in a race to release competing versions of “The Little Red Hen”. Action sequences now start to dominate our subject cartoon. Good use is made of a needle=drop of the Zampa Overture for a lively and dramatic underscore. (Knowing Iwerks’ consistent history of using recordings from Victor records in his films, I am speculating that the version used may be by the Victor Symphony Orchestra directed by Nat Shilkret, Victor 12 inch 35985, although I have never heard the record – input would be appreciated from anyone who can confirm.) Instead of a pylon, the racers round a halfway point denoted by a red flag placed into a floating cloud (an aeronautic achievement in and of itself). The villain and Willie take a short cut through a mountain railway tunnel, chasing a locomotive out the opposite end. The villain takes off his scarf, and lets it loose to wrap around Willie’s head, covering his eyes. Willie’s plane falls in a blind nose dive.

In an innovative shot (the only such type of shot I am aware of in an Iwerks’ production), Iwerks blends animation of Willie over a live-action shot of a tall tower being exploded, making it appear that Willie’s plane is the cause of the demolition. In another unique moment for the studio, an “in-joke” results from a swoop of the plane through the roof and awning of a fireworks shop, the plane’s propeller chopping up the lettering on the awning, so that it comes out spelling the name “Iwerks”! What a shame that audiences never got to publicly see these two creative gags in a row. Which were sure to have sparked a positive reaction. Willie finally gets the scarf out of his eyes, and finds that his plane has picked up a bundle of skyrockets on the wing. Shifting them to a position on the plane’s tail, Willie ignites the fuses. He begins to catch up at blinding speed, as the villain spurs on his own plane for a suspenseful race to the finish. The rocket power is just the extra boost Willie needs, and he collides prop first with the rear of the villain’s plane, and burrows a hole right through it, gutting the plane of its powerful engine and leaving only the pilot seat and fuselage shell. Willie lands with a bounce just over the finish line, with the wreck of the villain’s plane crashing down a split second later, throwing Willie from his cockpit. Willie lands in the prize loving cip held by Amelia Earhart, who places a floral horseshoe wreath around Willie’s neck, and plants a big kiss on Willie’s cheek. The scene dissolves back to the present, as Willie boasts about receiving the kiss. Life imitates art, as a horseshoe over the barn door falls to land around Willie’s neck, and Willie receives a kiss from a barnyard mule, while the other kids who have been listening to the tall tale laugh for the iris out.

In an innovative shot (the only such type of shot I am aware of in an Iwerks’ production), Iwerks blends animation of Willie over a live-action shot of a tall tower being exploded, making it appear that Willie’s plane is the cause of the demolition. In another unique moment for the studio, an “in-joke” results from a swoop of the plane through the roof and awning of a fireworks shop, the plane’s propeller chopping up the lettering on the awning, so that it comes out spelling the name “Iwerks”! What a shame that audiences never got to publicly see these two creative gags in a row. Which were sure to have sparked a positive reaction. Willie finally gets the scarf out of his eyes, and finds that his plane has picked up a bundle of skyrockets on the wing. Shifting them to a position on the plane’s tail, Willie ignites the fuses. He begins to catch up at blinding speed, as the villain spurs on his own plane for a suspenseful race to the finish. The rocket power is just the extra boost Willie needs, and he collides prop first with the rear of the villain’s plane, and burrows a hole right through it, gutting the plane of its powerful engine and leaving only the pilot seat and fuselage shell. Willie lands with a bounce just over the finish line, with the wreck of the villain’s plane crashing down a split second later, throwing Willie from his cockpit. Willie lands in the prize loving cip held by Amelia Earhart, who places a floral horseshoe wreath around Willie’s neck, and plants a big kiss on Willie’s cheek. The scene dissolves back to the present, as Willie boasts about receiving the kiss. Life imitates art, as a horseshoe over the barn door falls to land around Willie’s neck, and Willie receives a kiss from a barnyard mule, while the other kids who have been listening to the tall tale laugh for the iris out.

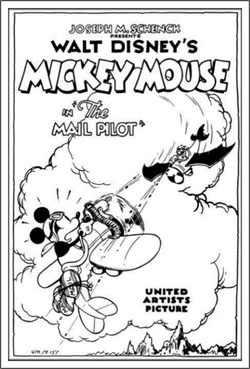

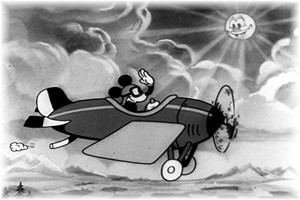

The Mail Pilot (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 5/13/33 – David Hand, dir.), finds Mickey has not let the past five years go by without continuing to forge ahead in his love of aircraft. He is now a certified pilot, entrusted with the important responsibility of carrying mail so important, it is delivered to him in an armored car accompanied by a small squad of armed security personnel. Mickey’s plane is fairly up to date in design, with some aerodynamic sense and streamlining, and contains at least one custom control on the dashboard – a button which reveals a portrait of his beloved Minnie, framed in her good luck horseshoe left over from Plane Crazy. Mickey seals the locked strongbox of mail inside his fuselage (by means of a convenient zipper). He also observes a wanted poster on a nearby wall, offering reward for a mail bandit (Pete, who else?). Mickey takes his oil can and launches five shots at the poster, which land just above Pete’s picture, then drip down, making Pete appear to be behind bars. Then Mickey is off, his plane’s landing gear running and hopping until lift is achieved.

The Mail Pilot (Disney/United Artists, Mickey Mouse, 5/13/33 – David Hand, dir.), finds Mickey has not let the past five years go by without continuing to forge ahead in his love of aircraft. He is now a certified pilot, entrusted with the important responsibility of carrying mail so important, it is delivered to him in an armored car accompanied by a small squad of armed security personnel. Mickey’s plane is fairly up to date in design, with some aerodynamic sense and streamlining, and contains at least one custom control on the dashboard – a button which reveals a portrait of his beloved Minnie, framed in her good luck horseshoe left over from Plane Crazy. Mickey seals the locked strongbox of mail inside his fuselage (by means of a convenient zipper). He also observes a wanted poster on a nearby wall, offering reward for a mail bandit (Pete, who else?). Mickey takes his oil can and launches five shots at the poster, which land just above Pete’s picture, then drip down, making Pete appear to be behind bars. Then Mickey is off, his plane’s landing gear running and hopping until lift is achieved.

Mickey runs into a rainstorm. Visibility is becoming obscured by the water on his flight goggles, so Mickey pushes a button on the goggle frame, producing a pair of windshield wipers to clear up the problem. His plane dodges lightning bolts, jumping over the top of them, then sawing one large bolt into a string of miniature ones with its propeller. Then comes a snowstorm. The plane is fringed with rows of icicles, but manages to thaw out when the smiling sun appears from behind the clouds. But ahead lies the real danger – Pete, in an evil looking black plane. Despite having no vertical rotor, Pete’s craft is remarkable for its ability to hover in mid-air, allowing Pete to climb out onto a rocky mountain crag and use it as a lookout station like an Indian warrior on a cliff in a cowboy Western. Spying the approaching mail plane, Pete returns to his cockpit, takes up a position ahead of Mickey’s plane, and goes into hover mode again, as Pete pulls a machine gun on Mickey, yelling, “Stick ‘em up!” Mickey’s plane responds by stalling in mid air and holding up its wings, but then makes a run for it. Pete is right on Mickey’s tail, and with his machine gun, trims Mickey’s wings off so that only about a foot of wing surface remains on both sides, then saws off Mickey’s propeller. The plane goes into a nose dive, plowing across the roof shingles of two barns, and bouncing off an out-building, to land with a thud next to an outdoor rotating clothes-drying pole with multiple arms. As Pete descends after him. Mickey uses what is available, sticking the clothes pole into the top of his rear fuselage, then tying the drying wash into a cloth loop, spooled around the pole shaft and his propellerless engine shaft. He starts the engine again, and achieves the effect of an instant autogyro, lifting the plane just out of the way of Pete’s dive. If Mickey had only remembered that the base of the clothes pole was not fastened down to anything. The pole thus spins out of the fuselage hole with a pop. Mickey tries to grab it, but merely gets spun around, then loses his grip and falls back into the cockpit, as the plane goes into a second dive.

But this time, Mickey acquires a more dependable power source, by repeating (or more likely originating) Willie Whopper’s feat of crashing into the blades of a farm windmill for a new propeller. As Mickey regains altitude, Pete flips a panel above his engine hood, replacing his machine gun with a harpoon gun. Launching a shot at Mickey, he gets a hook into the tail of Mickey’s plane. As Mickey struggles at his controls in attempt to get free, the picture of Minnie pops out as a last-minute inspiration. Mickey kisses the photo, and with a look of determination, hatches an idea. If he can’t free himself, why not take Pete with him? He shifts his plane into full throttle, and Pete finds himself unable to pull up or slow the speeding craft, thus being dragged along for the ride. Mickey makes it painful for Pete, by flying through a bell tower, fracturing Pete’s plane and tangling Pete up by the neck in the bell ropes, dragging a clanging mass of bells behind him. Then Mickey descends, dragging Pete’s bottom through thick brush on the ground. The airfield is just ahead, where more armed guards await. Mickey brings his plane to a halt on the runway, allowing the harpoon rope and Pete to slide by him. Pete’s weight is enough to rip the fabric off of Mickey’s ship as he passes, but Mickey’s mission is accomplished, and the guards wait with open mail sack for Pete to slide in, then pull the bag’s cords shut upon Pete’s neck, holding him prisoner at bayonet point. The skeleton of Mickey’s plane and the mail strongbox within are carried atop the shoulders of the postal guards in celebration, while Minnie appears among the throng, just in time to give Mickey the traditional kiss for the iris out.

But this time, Mickey acquires a more dependable power source, by repeating (or more likely originating) Willie Whopper’s feat of crashing into the blades of a farm windmill for a new propeller. As Mickey regains altitude, Pete flips a panel above his engine hood, replacing his machine gun with a harpoon gun. Launching a shot at Mickey, he gets a hook into the tail of Mickey’s plane. As Mickey struggles at his controls in attempt to get free, the picture of Minnie pops out as a last-minute inspiration. Mickey kisses the photo, and with a look of determination, hatches an idea. If he can’t free himself, why not take Pete with him? He shifts his plane into full throttle, and Pete finds himself unable to pull up or slow the speeding craft, thus being dragged along for the ride. Mickey makes it painful for Pete, by flying through a bell tower, fracturing Pete’s plane and tangling Pete up by the neck in the bell ropes, dragging a clanging mass of bells behind him. Then Mickey descends, dragging Pete’s bottom through thick brush on the ground. The airfield is just ahead, where more armed guards await. Mickey brings his plane to a halt on the runway, allowing the harpoon rope and Pete to slide by him. Pete’s weight is enough to rip the fabric off of Mickey’s ship as he passes, but Mickey’s mission is accomplished, and the guards wait with open mail sack for Pete to slide in, then pull the bag’s cords shut upon Pete’s neck, holding him prisoner at bayonet point. The skeleton of Mickey’s plane and the mail strongbox within are carried atop the shoulders of the postal guards in celebration, while Minnie appears among the throng, just in time to give Mickey the traditional kiss for the iris out.

Betty Boop’s Big Boss Fleischer/Paramount, Betty Boop, 6/2/33 – Dave Fleischer, dir., Bernard Wolf,/David Tendlar, anim.), deserves honorable mention. The majority of the film revolves around Betty’s application for an office secretarial job. She is considerably more flirtatious than usual, admitting when asked “What can you do?” that she’s nothing at all in either typing or answering phone calls, but in a Morris chair or on his knee, she musically informs him “You’d be surprised.” She is instantly hired, while all other applicants are ejected through a trap door. The boss has anything but office business on his mind in his plans for Betty, picturing himself receiving kisses and embraces from her in a thought cloud. Before long, he cannot hold back his instincts, and advances toward her. Betty heads for the exit, but the door grabs up its own key with its doorknob, and swallows it through the mail chute, locking Betty in. Betty places a desperate phone call for help, which brings out troops from the army, navy, air corps, and local police The air corps respond in a V-shaped flying formation of biplanes. However, their precision flying is disrupted when a passing bird flies in front of them, and the planes respond as if the bird is their flock leader, following him in a circle around the screen until he exits the frame, then regroup into their flying formation. By the time the troops and cops finally reach Betty (by cutting away the tall office tower with a hail of bullets at the foundation, sinking the boss’s office to ground level), the windowshade flips up, revealing Betty locked in an embrace with the boss, and actually liking it. Seeing the onlookers at the window, she yells at them, “Fresh”, and pulls the windowshade, leaving her would-be rescuers to mutter, “How do you like that?”

Hypnotic Eyes (Terrytoons/Educational, 8/1/33) – Chapter 4 in animation’s first (and only) serialized melodrama, featuring heroine Fanny Zilch, the banker’s daughter, hero J. Leffingwell Strongheart, and the villainous Oil Can Harry (a silk-hatted, moustached human, not yet the cat he would be fashioned into for his rebirth in the Mighty Mouse cartoons of the 1940’s.) Everything is pretty much the same as you’d expect in any Terry melodrama spoof, with preposterous perils, improbable rescues, and a helpless heroine always at the villain’s mercy. In fact, this one seems more familiar than usual, contributing an idea which would be reworked into the premise of Mighty Mouse’s “Svengali’s Cat”, having Fanny hypnotized by the villain and made to sing, arbitrarily choosing for her number the ancient (and presumably public domain) tune, “Ben Bolt”. Strongheart rides to the rescue atop a white stallion, accompanied by his dog (a variant on what would eventually become Puddy). Oil Can shoots from inside his hideout through the door, peppering Strongheart’s chest with bullet holes. But the dog easily effects first aid by sucking out the bullets with a plunger (never mind the details of healing over the holes and internal damage). Oil Can takes to the air with Fanny aboard a private plane, launching itself with flapping wings. Strongheart’s dog trims the tail of his horse and gives the tail a spin, serving as a rotor to propel the horse into the sky. As Strongheart attempts to intercept the plane, Oil Can pulls some neat tricks to avoid collision, by splitting the plane in two, both in horizontal and vertical splits, allowing the horse to sail right through and past. Meanwhile, the dog sends out alarms by retrieving from his doghouse an alarm clock tied to his tail. Somehow, without a word, this signal is understood by of all people, Charlie Chaplin, who blows a police whistle to summon the cops (who for no reason ride in a vehicle that more closely resembles am endlessly-long hook and ladder truck.) Another arbitrary trio of characters make cameos, including a long-nosed celebrity chomping a cigar (please identify, if you can), Joe E. Brown, and Jimmy Durante. But all of this public arousal is entirely unnecessary, and pure space filler, as Strongheart saves the day by landing his horse on a cloud, then having his mount throw off two horseshoes with a powerful kick, which score a direct hit on Oil Can’s plane, bringing it down. “Curses”, said Oil Can, thrown from the wreckage as his plane goes up in flames. Fanny is reunited with Strongheart for an embrace, and the iris out.

World Flight (Harman-Ising/RKO, Cubby Bear, 8/24/33, I. Freleng/Paul Smith, anim.). Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising (who receives entirely misspelled credit in the titles as “Isling”) were between studios, having gotten the boot from Leon Schlesinger, and not yet finding an open door at MGM. They thus resorted to farming out their labors for hire, finding an opening at RKO/Pathe to supplement the output of the Van Buren studios, with their own take on the studio’s closest rival to Mickey Mouse, Cubby Bear. It quickly became apparent that Harman and Ising did not feel this assignment required any great degree of re-tooling to adapt to, as their portrayal of Cubby (a character largely without personality anyway) is nothing more that a revisit by Bosko or Foxy, performing in a bear suit. The very first shot is straight out of stock pencil drawings, with a paper boy circulating copies of a late evening extra, in identical manner to a scene from “Battling Bosko”, announcing Cubby’s attempt to circumnavigate the globe. This same animation would be reused once more when the studio reached MGM, in “Bosko’s Parlor Pranks”. The real feat of a world flight had already been accomplished by four U,S, Army planes in 1924. Cubby strolls at the airstrip to the cheers of the crowd, in animation modified from Foxy’s cantina entrance in “Lady, Play Your Mandolin”. A quartet of crowd control officers turn out to be the four Marx Brothers, who sing in Cubby’s praise as Cubby reaches his aircraft, the “Spirit of America”. (No one is supposed to notice that Harpo is singing, although he was always portrayed as a mute in his actual film performances.) Also showing up at the field is Lindbergh himself, along with the Spirit of St. Louis, which walks behind him under its own power. Lindy exchanges a handshake and wish of good luck to Cubby, while the two planes also exchange a handshake with their landing gear. Paraphrasing from Mae West, Cubby tells Lindy, “Why don’t you come up sometime?” (strangely beating Iwerks to the punch on this line, due to the withdrawal of “The Air Race” from the market). Cubby’s new variant on turning the prop has the prop shaft somehow connected inside to the plane’s tail, twisting the fuselage into a spiral as Cubby turns the blades, then spinning backwards to straighten itself out, flipping Cubby into the pilot’s seat. After rhythmic engine sputters and two blasts of smoke out the exhaust pipe, the plane takes off in running fashion, each step timed to the tune of “Yankee Doodle”.

World Flight (Harman-Ising/RKO, Cubby Bear, 8/24/33, I. Freleng/Paul Smith, anim.). Hugh Harman and Rudolf Ising (who receives entirely misspelled credit in the titles as “Isling”) were between studios, having gotten the boot from Leon Schlesinger, and not yet finding an open door at MGM. They thus resorted to farming out their labors for hire, finding an opening at RKO/Pathe to supplement the output of the Van Buren studios, with their own take on the studio’s closest rival to Mickey Mouse, Cubby Bear. It quickly became apparent that Harman and Ising did not feel this assignment required any great degree of re-tooling to adapt to, as their portrayal of Cubby (a character largely without personality anyway) is nothing more that a revisit by Bosko or Foxy, performing in a bear suit. The very first shot is straight out of stock pencil drawings, with a paper boy circulating copies of a late evening extra, in identical manner to a scene from “Battling Bosko”, announcing Cubby’s attempt to circumnavigate the globe. This same animation would be reused once more when the studio reached MGM, in “Bosko’s Parlor Pranks”. The real feat of a world flight had already been accomplished by four U,S, Army planes in 1924. Cubby strolls at the airstrip to the cheers of the crowd, in animation modified from Foxy’s cantina entrance in “Lady, Play Your Mandolin”. A quartet of crowd control officers turn out to be the four Marx Brothers, who sing in Cubby’s praise as Cubby reaches his aircraft, the “Spirit of America”. (No one is supposed to notice that Harpo is singing, although he was always portrayed as a mute in his actual film performances.) Also showing up at the field is Lindbergh himself, along with the Spirit of St. Louis, which walks behind him under its own power. Lindy exchanges a handshake and wish of good luck to Cubby, while the two planes also exchange a handshake with their landing gear. Paraphrasing from Mae West, Cubby tells Lindy, “Why don’t you come up sometime?” (strangely beating Iwerks to the punch on this line, due to the withdrawal of “The Air Race” from the market). Cubby’s new variant on turning the prop has the prop shaft somehow connected inside to the plane’s tail, twisting the fuselage into a spiral as Cubby turns the blades, then spinning backwards to straighten itself out, flipping Cubby into the pilot’s seat. After rhythmic engine sputters and two blasts of smoke out the exhaust pipe, the plane takes off in running fashion, each step timed to the tune of “Yankee Doodle”.

Cubby’s first problem is an inability to gain any degree of elevation. A clever shot has Cubby buzz the tops of a row of trees, several of which have already seasonally lost their leaves, while the second half of the row remains evergreen. Cubby’s close brush with his propeller shaves all the leaves off the evergreens, depositing them on the trees that were bare. He next plows through a wheat field, where his prop converts cut wheat into neat haystacks (a gag lifted from Disney’s “Birds in the Spring”, where a swarm of bees accomplished the same thing). He collides nose-first with a tree trunk, the propeller sawing the tree piece by piece into a neat stacked pile of logs. He inadvertently engages in the stunt flyer’s pastime of “barnstorming”, flying his plane tight into and through the open doors of a barn, temporarily picking up a flock of chickens as passengers, and nearly running down a cow. Finally, his plane hooks onto a farm’s picket fence, uprooting the whole thing post by post, and taking with him the attached farmhouse, windmill, and outbuilding.

Cubby’s first problem is an inability to gain any degree of elevation. A clever shot has Cubby buzz the tops of a row of trees, several of which have already seasonally lost their leaves, while the second half of the row remains evergreen. Cubby’s close brush with his propeller shaves all the leaves off the evergreens, depositing them on the trees that were bare. He next plows through a wheat field, where his prop converts cut wheat into neat haystacks (a gag lifted from Disney’s “Birds in the Spring”, where a swarm of bees accomplished the same thing). He collides nose-first with a tree trunk, the propeller sawing the tree piece by piece into a neat stacked pile of logs. He inadvertently engages in the stunt flyer’s pastime of “barnstorming”, flying his plane tight into and through the open doors of a barn, temporarily picking up a flock of chickens as passengers, and nearly running down a cow. Finally, his plane hooks onto a farm’s picket fence, uprooting the whole thing post by post, and taking with him the attached farmhouse, windmill, and outbuilding.

A global map view of the USA shows Cubby’s progress – with a clever detour as Cubby almost encounters machine-gun fire emanating from the gangster territory of Chicago. Cubby makes the climb over a tall desert peak with the help of a prod from a cliffside cactus into his plane’s rear end. His vertical descent on the other side is more rapid, boring a hole in the ground. He burrows clean through the earth’s core, passing Satan in his lair, who shouts , “What the h—.” Cubby pops out upside down in China (so doesn’t that mean he cheated, actually flying only halfway around the world, by skipping Hawaii, Japan, and the whole Pacific?) He is met by local Chinese dignitaries, who deliver a speech in mock Chinese, ending with Ed Wynn’s catch-word, “So-o-o-o-ooo”. Cubby responds for no goof reason with the catch phrase of radio’s Baron Munchausen (Jack Pearl) – “Vas you dere, Charlie?” Cubby takes off again, and is now seen looking down from atop his plane upon a rotating global view of various countries, including Russia, Germany (complete with singing caricatures of Adolf Hitler and possibly Goering and another of his principal officers), and France (where a statue of Napoleon transforms into a singing Maurice Chevalier). Cubby embarks on the last leg of his journey across the Atlantic, but encounters a storm system determined not to let him complete his mission. Lightning bolts form into the shape of a hand performing a deriding nose-wave from the face of a cloud, while another cloud’s face breathes lightning bolts like a fire-breathing dragon. The bolts drill into the plane’s tail, zip between the plane’s legs, then form into circles with their jagged edges extended like buzzsaw blades, sawing the wings off Cubby’s plane. As the plane begins to droop and pitch aimlessly, Cubby solves the lift problem by grabbing a pair of passing geese by the feet, setting them on the stubs of each wing and getting them to flap. But the storm won’t give up, and repeats the action from Bosko’s “Dumb Patrol”, first blasting away the fabric from the plane with a lightning strike, then obliterating the plane itself with another. It looks like Cubby’s finish, but he has just reached his destination, and lands on one of the prongs of the crown of the Statue of Liberty, who comes to life, places Cubby on the pedestal surrounding her torch, and sings Cubby’s praises in a surprising basso voice, while the whole of Manhattan Island shouts in response (including a noticeable King Kong clinging to the Empire State Building), for the iris out.

A global map view of the USA shows Cubby’s progress – with a clever detour as Cubby almost encounters machine-gun fire emanating from the gangster territory of Chicago. Cubby makes the climb over a tall desert peak with the help of a prod from a cliffside cactus into his plane’s rear end. His vertical descent on the other side is more rapid, boring a hole in the ground. He burrows clean through the earth’s core, passing Satan in his lair, who shouts , “What the h—.” Cubby pops out upside down in China (so doesn’t that mean he cheated, actually flying only halfway around the world, by skipping Hawaii, Japan, and the whole Pacific?) He is met by local Chinese dignitaries, who deliver a speech in mock Chinese, ending with Ed Wynn’s catch-word, “So-o-o-o-ooo”. Cubby responds for no goof reason with the catch phrase of radio’s Baron Munchausen (Jack Pearl) – “Vas you dere, Charlie?” Cubby takes off again, and is now seen looking down from atop his plane upon a rotating global view of various countries, including Russia, Germany (complete with singing caricatures of Adolf Hitler and possibly Goering and another of his principal officers), and France (where a statue of Napoleon transforms into a singing Maurice Chevalier). Cubby embarks on the last leg of his journey across the Atlantic, but encounters a storm system determined not to let him complete his mission. Lightning bolts form into the shape of a hand performing a deriding nose-wave from the face of a cloud, while another cloud’s face breathes lightning bolts like a fire-breathing dragon. The bolts drill into the plane’s tail, zip between the plane’s legs, then form into circles with their jagged edges extended like buzzsaw blades, sawing the wings off Cubby’s plane. As the plane begins to droop and pitch aimlessly, Cubby solves the lift problem by grabbing a pair of passing geese by the feet, setting them on the stubs of each wing and getting them to flap. But the storm won’t give up, and repeats the action from Bosko’s “Dumb Patrol”, first blasting away the fabric from the plane with a lightning strike, then obliterating the plane itself with another. It looks like Cubby’s finish, but he has just reached his destination, and lands on one of the prongs of the crown of the Statue of Liberty, who comes to life, places Cubby on the pedestal surrounding her torch, and sings Cubby’s praises in a surprising basso voice, while the whole of Manhattan Island shouts in response (including a noticeable King Kong clinging to the Empire State Building), for the iris out.

An interesting final note is that, within the next year, Van Buren’s home-grown talent, in what may have been professional jealousy, attempted their own rival airborne epic Cubby’s Stratospheric Flight. However, not only does their film not feature an actual plane (placing it outside the scope of this article), but its plot is hopelessly random and jumbled, spending 90% of its time on the ground after the flight has already failed, and looks more like something produced a good two to three years earlier than its actual production date, as a mere excuse to animate some musical numbers. Clearly, the West coast artists could fly circles around the East coast artists when it came to a head-to-head battle for production quality.

When Yuba Plays the Rumba on the Tuba (Fleischer/Paramount, Screen Song, 9/15/33, Dave Fleischer, dir., Bernard Wolf/Thomas Johnson, anim.) is in essence a double feature of two short cartoons on one reel, set to the lively rhythms of the Mills Brothers. The first half deals with the flight of a dirigible, while the second half is an unrelated mini-cartoon following a railroad hand car trying to outrace a locomotive. (The middle section, in which the Mills Brothers would have performed in live action, is excised from the currently-circulating print.)

In the opening, the dirigible is inflated by means of an elephant’s trunk attached to its air nozzle, with air forced from the elephant by compressing his tail like a bicycle pump. A crewman gives the nose propeller a spin, is sucked into the prop, and has various articles of his clothes thrown off without him, finally reduced to his underwear as the clothes disappear into the prop again. At a small field dressing room, passengers enter through one door, and just as quickly exit from the other side, wearing pilot’s suits for high altitude travel. The ship is launched by three crewmen lifting the light vessel bodily off a mounting, turning it sideways so that the bottom of the passenger gondola resembles the stitching on the side of a football, and throwing the airship for a “forward pass”. Passengers peer out of the gondola windows with spyglasses, each of which tie themselves in knots around the others. The captain sees a cloudbank looming ahead, where two clouds battle it out like boxers. One cloud falls, and the other squeezes him dry, wringing the water out of him upon the airship. A gag is directly lifted from Tom and Jerry’s “Trouble”, as a second cloud smokes the dirigible like a giant cigar. A small bird tries desperately to stop up holes that appear in the top of the dirigible’s “skin”, but the balloon deflates until it looks like the blackbird pie from “Six a Song of Sixpence” after the virds escaped. The passengers still continue to propel the craft by extending oars out the gondola windows and rowing. A pig leaps out the gondola door wearing a parachute. However, his ripcord detaches from the chute, revealing the cord is a stem attached to a funeral lily. The pig scrambles through air back to the gondola, to be handed an umbrella to replace his chute. The segment ends abruptly, as four characters sail down to earth, possibly transforming upon landing into aviator versions of the Mills Brothers themselves.

King Klunk (Lanuz/Universal, Pooch the Pup, 9/4/33) is a mini-epic, presenting a direct parody upon the blockbuster, “King Kong”, which, of course, necessitates the inclusion of airplanes – actually only one, Pooch himself taking on the duties of an entire squadron. The giant ape Klunk is smitten by one too many arrows from a native Dan Cupid, and has fallen into a state of “Goona-Goona” over Pooch’s girlfriend. This exotic reference refers to the title of a 1932 exploitation film/melodrama set in Bali, which became synonymous with pre-code (and even post code) films finding excuses to show topless native females. The phrase roughly translates as an evil love spell cast upon an unwilling victim. Klunk breaks free from his chains in the theater where he is on display, and lifts up the entire building over his head as the patrons flee. Pursuing the crowd, he scoops up handfuls of them in search of his lady love, and tosses away the ones that don’t include her. Once the girl is located, he of course climbs the tallest tower – in this instance, the Broken Arms Apartments. His climb is laugh provoking, as each step is accompanied by an upward grip on the building, squeezing the structure in his mighty hands so that tenants of each apartment are jetted out of the windows. Atop the tower, Klunk pulls up his chest fur as if it were a shirt, revealing a giant bass drum affixed to his chest, for him to pound on with his fists as a sign of booming victory. Pooch of course must effect a rescue, and from nowhere locates a convenient plane. He spins the prop, but the whole motor detaches from the plane’s nose, spinning Pooch on the propeller, then flattening him like a pancake into the trunk of a tree. The noseless plane develops eyes and a mouth, runs up to Pooch, then opens its jaws and bites down on the engine mount to hold it in place. One of its landing wheels transforms into a hand, which peels Pooch off the tree and places him in the cockpit, then spins the plane’s own propeller for a take-off. Pooch isn’t much of a pilot.

King Klunk (Lanuz/Universal, Pooch the Pup, 9/4/33) is a mini-epic, presenting a direct parody upon the blockbuster, “King Kong”, which, of course, necessitates the inclusion of airplanes – actually only one, Pooch himself taking on the duties of an entire squadron. The giant ape Klunk is smitten by one too many arrows from a native Dan Cupid, and has fallen into a state of “Goona-Goona” over Pooch’s girlfriend. This exotic reference refers to the title of a 1932 exploitation film/melodrama set in Bali, which became synonymous with pre-code (and even post code) films finding excuses to show topless native females. The phrase roughly translates as an evil love spell cast upon an unwilling victim. Klunk breaks free from his chains in the theater where he is on display, and lifts up the entire building over his head as the patrons flee. Pursuing the crowd, he scoops up handfuls of them in search of his lady love, and tosses away the ones that don’t include her. Once the girl is located, he of course climbs the tallest tower – in this instance, the Broken Arms Apartments. His climb is laugh provoking, as each step is accompanied by an upward grip on the building, squeezing the structure in his mighty hands so that tenants of each apartment are jetted out of the windows. Atop the tower, Klunk pulls up his chest fur as if it were a shirt, revealing a giant bass drum affixed to his chest, for him to pound on with his fists as a sign of booming victory. Pooch of course must effect a rescue, and from nowhere locates a convenient plane. He spins the prop, but the whole motor detaches from the plane’s nose, spinning Pooch on the propeller, then flattening him like a pancake into the trunk of a tree. The noseless plane develops eyes and a mouth, runs up to Pooch, then opens its jaws and bites down on the engine mount to hold it in place. One of its landing wheels transforms into a hand, which peels Pooch off the tree and places him in the cockpit, then spins the plane’s own propeller for a take-off. Pooch isn’t much of a pilot.

As he sets the plane into a nose dive above the beast, he is unable to keep up with it, and only barely manages to catch the tail of the plane when he flies out of the cockpit, to clamber back into his seat. Pooch swoops the plane between Klunk’s legs multiple times, giving him a buzz with the plane’s propeller where it can be felt the most. Klunk grabs the aircraft, but Pooch proves to be slippery, and keeps popping out from between the ape’s fingers. Now Pooch employs some artillery, producing from the plane’s hood an oversized cannon. He fires about eight cannonballs at Klunk, but the ape expands his chest again, exposing the bass drum, off which the cannonballs bounce and rebound back at Pooch’s plane. In typical 1930’s animation inconsistency, the plane’s face, previously established as holding the motor in its mouth, now repositions the engine as if it is wearing it as a hat, moving the eyes and mouth below it so that the plane can register a shock-take as the cannonballs hit it in the rear end. Pooch hits another switch, replacing the cannon with a machine gun. This time, he circles to fire at Klunk’s opposite side, carving with his bullets the outline of a target on Klunk’s posterior. Then, Pooch aims his plane nose-first directly into Klunk’s rear, buzzing him with the prop again, and knocking him off the building. With no explanation, when Klunk hits the pavement far below, he explodes into flames like a fallen aircraft (he must have eaten some gassy food), and is reduced to a giant skeleton. The native Cupid reappears, repeating to Klunk’s bones the phrase, “Goona Goona”. Klunk respond by chomping on the love spirit with his remaining bony jaws, trapping Cupid in a prison of Klunk’s dental fangs, while Pooch and his rescued sweetheart share a little “Goona-Goona” of their own.

Spite Flight (Ub Iwerks, MGM, Willie Whopper, 10/14/33), Better to make use of some footage from the scrapped “The Air Race” than none at all. In a more contrived plot, Willie winds up in a conventional melodrama, trying to pay the mortgage on his girlfriend’s mom’s home by winning an air race $1,000 prize. The silk-hat villain (whose personality is expressed in a clever Fleischer-like transformation gag that converts his handlebar moustache into a wriggling snake) enters the race too, just to make sure Willie won’t win the prize. Of course, the two of them fly planes identical to the original “The Air Race” to permit the reuse of scenes from the former. A shot for shot analysis reveals numerous reuses verbatim of scenes from the original, or mild reworkings of same to match changes of characters or occasionally embellish a gag. The airfield scene again begins with a fade to black, then a transition to the shadow under a planes wing.

Line up at the starting line is a verbatim stock shot. Minor character alteration allows the new villain to again place chewing gum on the wheel of Willie’s plane, as the starter counts down. Willie’s scene while stuck at the post begins identically to the former film, but this time Willie grabs the loosened motor to use it as a lawn mower to cut the gum from the wheel. A group flying shot of the villain and other contenders is from stock footage. St. Peter is thumbing for a hitch again, but this time upon a random cloud, trying to reach the pearly gates. He still gives the finger to a plane that doesn’t pick him up – this time more prolonged than in the original. Then Willie actually gives him a lift, St, Peter riding on the plane’s tail, and providing Willie with a competitive edge by flapping his own wings to give Willie’s plane extra speed. As the villain’s plane is passed, St Peter turns to give the villain the finger again! Peter is dropped off at the pearly gates, but the villain zooms past. Willie catches up, and we get a mid-air repeat of the villain using Willie’s prop as an electric shaver – but without the cloud of smoke turning his face black. A brief shot of Willie passing a Jewish autogyro pilot is repeated from the original. Then, another gag is lifted from “The Mail Pilot”, as the villain squirts oil in Willie’s face, blacking out his flight goggles. Willie uses a forward lock of his hair as a windshield wiper to clear the goggles, muck as Mickey’s built-in wipers did for him. We repeat from stock footage the train tunnel gag. A new finale has the villain grab from a tree a hive of bees, and throw it at Willie like a grenade. Willie catches it, and places the hive inside his outboard motor, then straightens out the engine’s exhaust pipe to face forward like a machine gun barrel. He begins rapid fire of the bees at the villain’s plane. There they saw through both wings and reduce the propeller to stubs. The plane falls into a dive, and the villain is thrown from his seat amidst a swarm of bees, landing upside down in a trash can on the ground. Willie spots the mortgage sticking out of the villain’s pants pocket, and ejects a few more bees to lift the document from the pocket into the air. As Willie’s girlfriend and her Mom look on, Willie fires more bees at the now unrolled mortgage, punching through the document in holes the letters, “PAID”. The girlfriend and Mom reward Willie with kisses in the winner’s circle, for the iris out.

Line up at the starting line is a verbatim stock shot. Minor character alteration allows the new villain to again place chewing gum on the wheel of Willie’s plane, as the starter counts down. Willie’s scene while stuck at the post begins identically to the former film, but this time Willie grabs the loosened motor to use it as a lawn mower to cut the gum from the wheel. A group flying shot of the villain and other contenders is from stock footage. St. Peter is thumbing for a hitch again, but this time upon a random cloud, trying to reach the pearly gates. He still gives the finger to a plane that doesn’t pick him up – this time more prolonged than in the original. Then Willie actually gives him a lift, St, Peter riding on the plane’s tail, and providing Willie with a competitive edge by flapping his own wings to give Willie’s plane extra speed. As the villain’s plane is passed, St Peter turns to give the villain the finger again! Peter is dropped off at the pearly gates, but the villain zooms past. Willie catches up, and we get a mid-air repeat of the villain using Willie’s prop as an electric shaver – but without the cloud of smoke turning his face black. A brief shot of Willie passing a Jewish autogyro pilot is repeated from the original. Then, another gag is lifted from “The Mail Pilot”, as the villain squirts oil in Willie’s face, blacking out his flight goggles. Willie uses a forward lock of his hair as a windshield wiper to clear the goggles, muck as Mickey’s built-in wipers did for him. We repeat from stock footage the train tunnel gag. A new finale has the villain grab from a tree a hive of bees, and throw it at Willie like a grenade. Willie catches it, and places the hive inside his outboard motor, then straightens out the engine’s exhaust pipe to face forward like a machine gun barrel. He begins rapid fire of the bees at the villain’s plane. There they saw through both wings and reduce the propeller to stubs. The plane falls into a dive, and the villain is thrown from his seat amidst a swarm of bees, landing upside down in a trash can on the ground. Willie spots the mortgage sticking out of the villain’s pants pocket, and ejects a few more bees to lift the document from the pocket into the air. As Willie’s girlfriend and her Mom look on, Willie fires more bees at the now unrolled mortgage, punching through the document in holes the letters, “PAID”. The girlfriend and Mom reward Willie with kisses in the winner’s circle, for the iris out.

The 30s continue to produce a bounty of fabulous flying fantasies, next time.