“Check the booty, yo it’s kinda soft an’ / If you touch it you’re livin in a coffin / I’m in the ‘90s, you’re still in the ‘80s, right / I rock the mic, they say I’m not ladylike”

“Check the booty, yo it’s kinda soft an’ / If you touch it you’re livin in a coffin / I’m in the ‘90s, you’re still in the ‘80s, right / I rock the mic, they say I’m not ladylike”

—“You Can’t Play With My Yo-Yo” by Yo-Yo

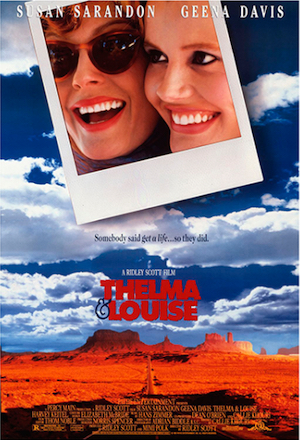

On May 24, 1991 – exactly as the above-quoted song debuted on the Billboard charts at #87 – a parallel but more wide-reaching pop culture event arrived. Ridley Scott’s THELMA & LOUISE isn’t the type of movie we normally think of as a summer blockbuster, but it was a phenomenon arguably bigger than most of the t-shirt and Slurpee selling spectacles I love to document in these retrospectives. A surprise hit, an Oscar winner, a capturer of the zeitgeist, it inspired months of back-and-forth editorials and feature articles, and was soon declared a watershed moment for women in movies. A genuine cultural moment.

On May 24, 1991 – exactly as the above-quoted song debuted on the Billboard charts at #87 – a parallel but more wide-reaching pop culture event arrived. Ridley Scott’s THELMA & LOUISE isn’t the type of movie we normally think of as a summer blockbuster, but it was a phenomenon arguably bigger than most of the t-shirt and Slurpee selling spectacles I love to document in these retrospectives. A surprise hit, an Oscar winner, a capturer of the zeitgeist, it inspired months of back-and-forth editorials and feature articles, and was soon declared a watershed moment for women in movies. A genuine cultural moment.

But I hadn’t re-watched it since that moment, and I really wasn’t sure how it would play now. It turns out when you remove it from any newness or perceived importance, it only emphasizes what an effective piece of entertainment it is.

We never hear how Thelma (Geena Davis, 3 years after winning an Oscar for THE ACCIDENTAL TOURIST) and Louise (Susan Sarandon, 20 years into her career, with BULL DURHAM a semi-recent highlight) know each other, but they’ve become a celebrated cinematic friendship thanks to their shared refusal to put up with anymore shit from men. Their rebellion comes in the form of a cross-country crime spree, but it starts as two friends just trying to get out of town to relax for a couple of days.

They live in Arkansas, Thelma is a housewife, and Louise works as a waitress, so they’re not planning an island getaway or some shit – they’re just driving to a cabin somewhere in the mountains where there’s fishing. Seems to be a vacation of opportunity: “It’s Bob’s, the day manager’s,” Louise explains. “He’s gettin’ a divorce, so his wife’s gettin’ this place, so he’s just lettin’ all his friends use it till he has to turn over the keys.”

They live in Arkansas, Thelma is a housewife, and Louise works as a waitress, so they’re not planning an island getaway or some shit – they’re just driving to a cabin somewhere in the mountains where there’s fishing. Seems to be a vacation of opportunity: “It’s Bob’s, the day manager’s,” Louise explains. “He’s gettin’ a divorce, so his wife’s gettin’ this place, so he’s just lettin’ all his friends use it till he has to turn over the keys.”

Louise needs a break because she’s “havin’ a nervous breakdown,” but she’s freer than her younger friend, with only an off-again boyfriend Jimmy (Michael Madsen right before RESERVOIR DOGS) who’s a touring guitar player. Thelma, on the other hand, is married to possessive, polyester-wearing buffoon Darryl (Christopher McDonald, BREAKIN’), who feels that as the regional manager of a carpet store chain he has earned the right to stay out late and expect her to stay home. She feels she has to ask him permission to take this trip, but chickens out and just leaves him a note – along with a microwaveable meal and a beer bottle with a little teddy bear attached to it.

When she reveals this to Louise they both laugh at the audacity of it. “He’s gonna kill you!” Louise says. It’s a proud moment of rebellion and also a lingering threat, a shitty consequence she knows she’ll have to face when the fun is over and she has to go back home. But (SPOILER TO A VERY FAMOUS MOVIE ENDING) it’s actually not anything she’ll ever have to deal with. So, no worries!

Thelma’s most fateful decision is insisting on bringing along Darryl’s gun which, as described in the script, she picks up “like it’s a rat by the tail,” but feels is needed in case of “psycho killers.”

Both the plot and our understanding of the characters hinge on their stopping for a drink at a crowded roadhouse. We see that Louise is the witty, wry one, and kind of uptight. She acts a little disapproving when Thelma orders a drink, but thinks better of it and and decides to join in the fun. She seems mostly annoyed, but slightly amused by Thelma’s willingness to flirt with a dude named Harlan (Timothy Carhart, PINK CADILLAC), who keeps hitting on her.

It seems like a long, fun night, but when Louise is ready to hit the road and goes to the restroom, Harlan drags a seemingly-drugged Thelma from the dance floor to the parking lot and tries to rape her, dropping his charming yokel routine and literally drooling as he slaps and insults her. Louise comes to her rescue with the aforementioned gun and, when Harlan insults them, shoots and kills him.

As they drive away, Louise holds the gun in her hands, staring at it. I think she realizes she didn’t need to kill him, and doesn’t take it lightly. Thelma wants to go to the police and explain what Harlan did to her. Louise’s counter-argument is one of the movie’s most salient points: “Just about a hundred people saw you dancing cheek to cheek with him all night, who’s going to believe that? We don’t live in that kind of a world, Thelma!”

(It occurs to me now that the makeup artist in MADONNA: TRUTH OR DARE who was similarly drugged and raped while out for drinks felt this way too. She had been drinking with them so she blamed herself. She didn’t have a Louise to stick up for her.)

Sadly, of course, we still don’t live in that kind of a world – those sorts of arguments are still used to question assault allegations. Another detail that I found very accurate and upsetting is the way the waitress who brings them their drinks (Carol Mansell, later in ED GEIN) acts toward Harlan. She knows him by name, and tries to shoo him away. Clearly she finds him a nuisance, always hitting on women, and tries to protect them from him. But she doesn’t know the extent of his shittiness, and/or doesn’t feel empowered to do much about it. I really think this is a guy who comes into the bar all the time, they all know him, think he’s sleazy and kind of funny, and meanwhile he must be putting things in other women’s drinks and assaulting them, and nobody stops him until Louise does.

Now their old lives are over. Instead of the cabin they head for Mexico, with some stops to try to get money. Louise’s boyfriend Jimmy is supposed to wire some money to her in Oklahoma, but surprises her by showing up in person. It’s a complicated relationship – she seems to still like him, even after he gets physically threatening, followed by a pathetic romantic gesture. But even when we’ve only seen his nice side we feel an uneasiness as to whether he’s a threat, echoing feelings Louise clearly has due to past experiences with men.

And famously we have J.D., a goofy hitchhiker who charms the pants off of Thelma as well as America, because it was the breakthrough role for one Brad Pitt, who had been on Growing Pains and Dallas, and in a few movies including CUTTING CLASS. There was a stretch after this when people thought he was some bland, brainless model type, but the character of J.D. is full of the kind of humor we know him for now, with some funny lines he reportedly improvised. Of course, the sex scene, when Scott and cinematographer Adrian Biddle (ALIENS, WILLOW) switch to the female gaze to admire his abs, probly had more to do with him becoming a sensation.

I think the look of the movie might be as crucial to its success as the story itself. Englishmen Scott and Biddle shoot American landscape and road iconography as if in awe of it, a perfect way to make these relatable characters feel mythical. As they traverse the highways of Arkansas, Oklahoma, Colorado and Arizona (mostly filmed in California and Utah), they are often surrounded by equipment: gigantic trucks, a cropduster flying over, oil pumps humping away at the earth, a herd of cattle bogging them down. Almost all the reviews I’ve read from the time mention this motif, sometimes making fun of it as a heavy-handed symbol of male power. I thought it was great, though. Yes, these are totems of what are thought of as rugged male industries, the opposite of Louise’s apron-wearing service industry job. But more importantly, what better symbol could there be for omnipresent masculine threats than getting boxed in by semis?

These things also just make for interesting visuals, as do many of the extras whenever they stop somewhere. I’m thinking, for example, of the authentic looking mob of women in the roadhouse restroom, crammed together doing their makeup in the mirror. Or some of the oddballs in the background of shots, my favorite being the random muscleman doing curls at the gas station.

Also notable: the score provided by Germany’s Hans Zimmer, particularly the main theme “Thunderbird,” with bluesy slide guitar by Pete Haycock of Climax Blues Band and Electric Light Orchestra Part II.

At times Thelma and Louise switch roles. While it was Louise’s fury that turned them into outlaws, it’s naive Thelma who decides to try her hand at armed robbery. Like the opening shot of the movie, their lives slowly go from black and white to vivid color as they feed off of each other and turn into this wish-fulfillment fantasy, refusing to compromise themselves or put up with any more bullshit. They unleash terror on dumb assholes who fuck with them, such as the truck driver (Marco St. John, THE PACKAGE) who keeps making obscene gestures at him until they blow up his gas trailer. Maybe the most thrilling line they cross is when they’re pulled over by a state trooper (Jason Beghe, MONKEY SHINES) who uses his scary demeanor against them when he thinks they’ve only been speeding, but turns into a blubbering mess when they overpower him and lock him in the trunk of his car. It cracks me up that Thelma mimics the way he talked to them: “You wanna step into the trunk, please?”

We also get more laughs with dipshit Darryl back home in Arkansas. When Thelma first calls him he’s outraged about her ditching him, but pays more attention to a football game on TV than to what she’s saying. Then he’s prepared to sell her out when the police come to his house with that only-in-the-movies scenario of having to keep her on the line for a certain amount of time to trace the call.

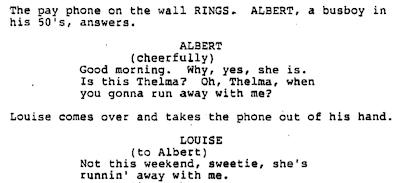

There are a couple of male characters who do not attempt to disrespect or screw over Thelma and Louise, but they include cabin-loaner Bob and another co-worker at the diner named Albert (who I was excited to recognize as Sonny Carl Davis, star of THE WHOLE SHOOTIN’ MATCH and LAST NIGHT AT THE ALAMO). But we never see Bob, and barely see Albert, and he still manages to jokingly hit on Thelma on the phone. I don’t actually know if they’re good or bad to Louise at work, I’m really just bringing them up as an excuse to mention the service industry solidarity of Louise leaving what she describes as a “huge tip” for the waitress at the roadhouse. It’s not underlined, but you know she tips well because she’s a waitress herself (as was screenwriter Callie Khouri before she broke into the film industry).

There are a couple of male characters who do not attempt to disrespect or screw over Thelma and Louise, but they include cabin-loaner Bob and another co-worker at the diner named Albert (who I was excited to recognize as Sonny Carl Davis, star of THE WHOLE SHOOTIN’ MATCH and LAST NIGHT AT THE ALAMO). But we never see Bob, and barely see Albert, and he still manages to jokingly hit on Thelma on the phone. I don’t actually know if they’re good or bad to Louise at work, I’m really just bringing them up as an excuse to mention the service industry solidarity of Louise leaving what she describes as a “huge tip” for the waitress at the roadhouse. It’s not underlined, but you know she tips well because she’s a waitress herself (as was screenwriter Callie Khouri before she broke into the film industry).

Harvey Keitel (in his followup to Alan Rudolph’s MORTAL THOUGHTS) as Detective Hal Slocumb is the only major male character who empathizes with Thelma and Louise and wants to help them. Keitel was about to reach a new level of recognition with RESERVOIR DOGS, and he’s a great, unorthodox choice to play the nice boy. But honestly I think the inclusion of such a character is the one part of the movie that seems a little timid. To me he plays like Tony Shalhoub in THE SIEGE, the token character to win over people who want to be sure the movie doesn’t think all men are jerks. From the reviews it’s clear that many people latched onto that at the time, but I think it actually dilutes the messages a little. Of course it’s not all men. But sometimes it doesn’t feel that way, and this is a movie more about how it feels than how it is. It takes place in a world where it’s always very sunny, or very rainy, or both. I don’t need a scene acknowledging that sometimes it’s mildly cloudy.

Which brings us to the ending. Surrounded by police cars in the Grand Canyon, they decide to “keep going” rather than surrender – meaning they drive off a cliff, and it famously ends in a poetic freeze frame as the car is in the air but not yet plummeting. In a 2011 NPR interview, Khouri explained why she saw it as a happy ending:

You know, to me, the end of the movie was never meant to be a literal they-drive-off-a-cliff-and-die kind of moment. It was a way of saying this was a world in which they didn’t believe there was the possibility of justice for them, that they didn’t believe that anyone would ever see their side of it enough to know why they had done what they’d done, and that this was just a way of letting them go and letting them stay who they were, who they had become. So I never saw it as a suicide. And over the years, hearing other people talk about it, I realize it’s like a half full, half empty glass of water test. You know, where some people will come up and go: I’m so glad you let them get away. And other people are like: I can’t believe you killed them. So, you know, to me, they got away.

If you, like me, wonder how they did that cliff jump, the answer is that they launched a car shell with dummies off a ramp. Check out the extended ending on the blu-ray or DVD to see a much more epic version of it, and to understand what an amazing shot they were willing to give up to make sure it played as triumph rather than tragedy.

Khouri wrote the script at the age of 30, while working as a line producer on music videos. She told Vanity Fair in 2011 that the whole story came to her while she was driving home from work one night in 1988. “I saw, in a flash, where those women started and where they ended up. Through a series of accidents, they would go from being invisible to being too big for their world to contain, because they’d stopped cooperating with things that were absolutely preposterous, and just became themselves.”

Khouri wrote the script at the age of 30, while working as a line producer on music videos. She told Vanity Fair in 2011 that the whole story came to her while she was driving home from work one night in 1988. “I saw, in a flash, where those women started and where they ended up. Through a series of accidents, they would go from being invisible to being too big for their world to contain, because they’d stopped cooperating with things that were absolutely preposterous, and just became themselves.”

The shooting was inspired by being mugged two times while working as a waitress in Nashville and then in L.A. and realizing that if she’d had a gun she would’ve killed them. In one of those incidents she was being walked to her car by Larry David (!), the other time she was with aspiring singer Pam Tillis, whose friendship inspired the relationship in the movie. Khouri saw herself as the Louise.

Khouri originally tried to produce the movie as a low budget indie directed by Julien Temple and starring Holly Hunter and Frances McDormand. The project was widely rejected, but they asked a friend named Mimi Polk for advice, she showed it to Scott, and he wanted to produce it. It was set to star Michelle Pfeiffer and Jodie Foster, then Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn, but Scott found that the directors he wanted (including Richard Donner) didn’t really get it, and in the process of trying to talk them into directing it, he instead talked himself into it.

Pitt got the part of J.D. only after William Baldwin dropped out to do fellow May 24th release BACKDRAFT, and a second choice whose name I couldn’t find left to do a TV show. When Davis auditioned with him she found him so cute she kept messing up her lines, but she had to convince Scott and the casting director that he was the one. Another great Geena Davis contribution to the film industry.

Due to one of the financiers committing massive fraud (long story), they ended up with less than half of their planned marketing budget, and then advertised it somewhat misleadingly:

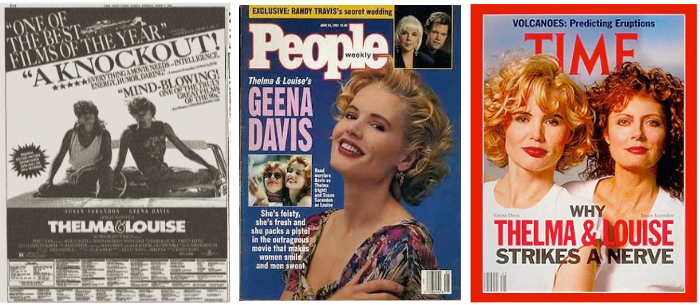

But that couldn’t stop it from catching on. It opened at #4, but stayed in the top ten through July 5th and ultimately almost tripled its $16.5 million budget in theaters. It later got Oscar nominations for best director, actress (for both Davis and Sarandon), cinematography and editing, and Khouri actually won for best original screenplay. A woman had won in this or equivalent earlier category only 8 times since 1928, and this was the first time it wasn’t shared with a male co-writer. In the 30 years after that there have been five more (Jane Campion for THE PIANO, Sofia Coppola for LOST IN TRANSLATION, Diablo Cody for JUNO and Emerald Fennell for PROMISING YOUNG WOMAN).

In today’s world of social media and short theatrical windows, even the biggest movies tend to be discussed mostly around their opening weekend, with a possible second round during awards season, and then they lay fallow unless they’re rediscovered later. But 1991 was a different time, and THELMA & LOUISE was an unusual movie, so even its initial response had three stages.

First, it opened to very positive reviews, though some writers (including Sheila Benson and Margaret Carlson) objected to the film being described as feminist and/or felt they were female characters simply acting out a male concept of empowerment through violence. Second, there was a backlash from conservative columnists calling it “male bashing” or “toxic.” So stage three was when the phenomenon of the movie’s popularity and controversy became a story in itself.

I’ve realized in retrospect that much of my idea of what was a big deal in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s came from my dad’s subscriptions to Newsweek and U.S. News & World Report. I think I knew THELMA & LOUISE was a phenomenon because Newsweek did a story not on opening weekend, but three weeks later, on June 19.

Their article called the film a “sleeper” and discussed its “ecstatic word of mouth” and “surprisingly virulent criticism” that “the two women commit too much social and moral damage to qualify as proper heroines or perfect feminists.” Echoing the 1985 comic strip that inspired what is now known as “The Bechdel Test,” the article notes that, “What seems to disquiet this movie’s critics is the portrayal of two women who, contrary to every law of God and popular culture, have something on their minds besides men.” It refers to Thelma and Louise’s decision to defend themselves from a rapist and blow up a harasser’s truck as a “new approach to being female.”

Another defense came in a June 12th Clarence Page Chicago Tribune column that likened the film to DO THE RIGHT THING and EASY RIDER. “Each was criticized justifiably for moral ambiguity, but each also became a movie milestone, a cinematic snapshot of its times.” On the 16th, Janet Maslin had a piece in the New York Times titled “Lay Off ‘Thelma and Louise’,” and by June 24th, Davis and Sarandon were on the cover of Time under the headline “WHY THELMA & LOUISE STRIKES A NERVE.”

All of these defenses cite complaints from Suzanne Fields, Richard Johnson of the New York Daily News, and especially a June 10th installment of John Leo’s On Society column in U.S. News titled “Toxic Feminism on the Big Screen.”

In the column, Leo claims that “a strong and extremely successful woman in the movie business” called to tell him that THELMA & LOUISE was “a very disturbing film and [he] must write about it immediately.” While swearing that “few of us would begrudge women two hours of male comeuppance” and acknowledging that the film is not very violent compared to movies starring men, he frets that “once we identify with the likable Thelma and Louise and the legitimacy of their complaints about men, we are led step by step to accept the nihilistic and self-destructive values they come to embody. By the time this becomes clear it is very difficult for moviegoers, particularly women, to bail out emotionally and distance themselves from the apocalyptic craziness that the script is hurtling toward.”

He goes on to describe the character of Thelma as a “ditsy housewife” and “scatterbrained near-victim of rape,” complain about Andrea Dworkin essays, and chastise “most of the reviewers” for praising a movie with “an explicit fascist theme,” an “extremely toxic film, about as morally and intellectually screwed up as a Hollywood movie can get” and “cynical propaganda.”

I like that Page’s column about the movie addresses its final two paragraphs directly to Leo:

But some women also find this movie’s feminist roller-coaster ride to be a bit too wild, John Leo writes. “A colleague at this magazine said she could not come to terms with the themes and ideas so blithely unleashed in this movie, and that many of the women who sat in the audience with her seemed to leave the theater in something of a daze.’

On the other hand, a woman I know whose attempted abduction and rape almost 20 years ago remains one of her most vivid memories thought the movie spoke volumes. Maybe those women coming out of the theater weren’t in a daze after all, John. Maybe their eyes were adjusting to the light.

That DO THE RIGHT THING comparison may have been more apt than he realized, because it would be hard to explain to a young person just how controversial the movie was then, but also you worry that its recognition as an Important Movie will make them assume it’s homework, when I really think it’s a fun one they would enjoy watching. Though it’s obviously a very famous movie that people know about – or at least they know about jumping off the cliff – it’s not one I hear come up in conversation very often. However, a good sign of its ongoing relevance is the number of books published about it in subsequent decades. They include Thelma & Louise and Women in Hollywood by Gina Fournier (2007), Thelma & Louise Live!: The Cultural Afterlife of an American Film edited by Bernie Cook (2007), Off the Cliff: How the Making of Thelma & Louise Drove Hollywood to the Edge by Becky Aikman (2017), a BFI Film Classics monograph by Marita Sturken (2020), and more*.

In 2016 it was selected for preservation in the Library of Congress National Film Registry, and Wikipedia lists its release as the fifth event on a timeline of Third-wave feminism, along with a quote from a 2011 New York Times article: “It took all those feelings of alienation and anger— which until that point had mostly found expression in things like ‘Take Back the Night’ rallies— and turned them into something rebellious, transgressive, iconic, punk rock and mainstream.”

Khouri followed her triumphant screenwriting debut with SOMETHING TO TALK ABOUT (1995) before writing and directing DIVINE SECRETS OF THE YA-YA SISTERHOOD (2002) and the TV movie HOLLIS & RAE (2006). MAD MONEY (2008) is the one movie she directed based on someone else’s screenplay. She’s since returned to her Tennessee days by creating, writing and directing for the show Nashville – which featured Thelma-inspiration Pam Tillis, now a well known country singer, as herself – and the TV movie PATSY & LORETTA. (Always coming back to that two women and an ampersand formula, I see.)

Scott’s next films were 1492: THE CONQUEST OF PARADISE (1992) and WHITE SQUALL (1996) before returning to conversation-starters-about-strong-defiant-women with 1997’s G.I. JANE.

The year after THELMA & LOUISE, main theme guitarist Pete Haycock composed the score for Carl Franklin’s ONE FALSE MOVE, and he subsequently played on five more Zimmer scores (K2, TOYS, TRUE ROMANCE, DROP ZONE, THE DILEMMA).

John Leo, the U.S. News writer who felt THELMA & LOUISE would seduce women into nihilism and self destruction, later – of fucking course – wrote books called Two Steps Ahead of the Thought Police and Incorrect Thoughts and is Editor-Emeritus of Minding the Campus, a non-profit websight which “aims to expose the single-lane thought highway at today’s universities and find solutions to the growing monoculture of ideas that silences.”

And finally I want to note that in 2007 Davis launched the Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, after having sponsored the largest ever research project on gender in children’s entertainment, which showed that there were nearly three males to every one female character in 400 movies they studied. She won an honorary Oscar for her work attempting to increase the presence of female characters and reduce stereotyping in media aimed at children. We don’t live in that kind of a world, but maybe we could some day.

*as a self-published author I can’t slag on self published authors, but check out these titles of other books I spotted on Amazon:

Thelma & Louise: The Explain Why Became Willing To Die With Each Other: The Bad Luck Of Thelma by Alethia Manko

Get Away From The Mediocre Lives: The Luck Of Friendship of Thelma & Louise: The Power of Durable Friendship by Brian Holmen

The Strength of Friendship: The Story Of Best Friends Thelma & Louise: A Story About Friendship And Love by Julius Strano

Thelma & Louise: The Explain Why Became Willing To Die With Each Other: The Cruel Life For Girls by Aurora Merisier

The Strength Of Friendship: The Story of Best Friends Thelma & Louise: The Art of Friendship Thelma & Louise by Ian Rocasah

Get Away From The Mediocre Lives: The Luck Of Friendship Of Thelma & Louise: The Cruel Life For Girls by Jerald Deshler

Coincidentally these six completely unrelated books by separate authors were all published on the 18th or 19th of this month.

There’s also what appears to be an unauthorized novelization by Jose Escobar, who has done the same for NEWSIES, X-FILES: FIGHT THE FUTURE, THE PLANET OF THE APES [sic], SOUTH PARK: BIGGER, LONGER AND UNCUT and THE MATRIX RELOADED. I used to genuinely think about writing a novelization of ON DEADLY GROUND, but thought it would be too much work to put into something that could likely be shut down. I’m guessing that’s not an issue with this guy’s books, though, whatever they are.