“Do you hear them singing?” my father asked.

I wished I could tell him yes.

“I can’t make out the song, but it’s something from before the war.” Beneath his blanket, my father shrugged. “Must be some new gimmick—they send a group of fellas around to all the condos, singing from door to door.”

Christmas had passed a few months earlier. My father lay dying in the hospital bed we had set up in my parents’ den. This was Boca Raton, in southern Florida. It was ninety degrees outside. Not only were there no carolers going from door to door, all but one or two of the retired couples who lived in my parents’ development were Jews. The hospice doctor said the cancer in my father’s lungs was depriving his brain of oxygen. “He will hallucinate more and more. Then, toward the end, he will see people he knew and loved from long ago. That’s how you’ll know that he’s nearly gone.”

I turned up the dial on the oxygen machine, but my father’s breathing came in ragged gasps. He would wheeze, then choke, at which my mother and I would try to argue him into letting us put a drop of morphine beneath his tongue. The nurses assured us the morphine would allow my father’s diaphragm to relax and ease his breathing. But he refused to take the drug because the morphine might cloud his brain, the irony being that the lack of oxygen was leading him to hallucinate.

My father never had the slightest use for drugs, except for the Novocaine he injected to dull other people’s pain. The only alcohol he ever drank was the finger of Manischewitz he poured in a juice glass to enjoy on a Friday night, smacking his lips and sighing at how sweet a man’s life could be. Every year, his patients would show their appreciation by giving him fine liqueurs; the bottles stood gathering dust on the top shelf of our pantry, so every time I sneaked in to steal more than my daily allowance of Tootsie Rolls or licorice sticks (I was a dentist’s daughter, after all), a tall, stiff porcelain soldier filled with something yellow and vile looked down in disapproval.

My father wanted me to succeed as a writer, but he couldn’t imagine a life in which a person sat around all day inventing stories.Once, my friend’s older brother, Preston, went to my father to get his teeth cleaned. “Gee,” my father said, “your teeth are kind of discolored. Do you smoke?” “Uh, not really,” the young man said. “Except, you know, some pot.” That anyone would so casually admit to smoking marijuana—which, to my dad, was a pharmaceutical of the same brain-destroying powers as LSD or heroin—blew my father’s mind. He repeated the story for years without understanding why, of all the jokes he told, this one got the fewest laughs, especially from his kids.

My father was resolutely opposed to any substance that altered a person’s ability to judge reality. His favorite advice was: “Use your head.” If anyone got sentimental, he muttered: “Cut the bullshit.” My mother and I are such creative dreamers we would happily spend the entire morning recounting our adventures of the night before, but my father could never recall a single dream. He wanted me to succeed as a writer, but he couldn’t imagine a life in which a person sat around all day inventing stories. His greatest pride was in his ability to look into a patient’s mouth and fix what needed fixing. A man couldn’t afford to daydream while maneuvering a high-speed drill.

His only form of fantasy was the kind of deadpan “true story” that wasn’t true. (You would be amazed how many people believed a patient showed up at his office one day with a billiard ball stuck behind his teeth and my father had no choice but to insert a cue stick you-know-where to poke it out.) After so many years listening to stand-up comics perform their shtick at his parents’ Borscht Belt hotel, my dad had developed an encyclopedic repertoire of dirty jokes, which he combined with a disarmingly sweet delivery that provided an ironic contrast to the vulgar nature of what he said. (My father so resembled the comedian Red Buttons that people used to stop him on the street and ask for his autograph, which my father sometimes gave. Oddly, Red Buttons died just a few months after my dad, and we learned from his obit that he and my father had been born a few months apart, a coincidence my father would have loved, if only we could have told him.)

You might assume this regular routine made him a caricature of the dentist who gets you in his chair, renders you immobile and mute, then regales you with tasteless jokes. But if you had asked my father who he was, he would have told you that he was a practical, straight-talking man who was good with his hands, treated everyone as his equal, and liked to make people laugh. Which assessment, I suspect, most people who knew him would agree was true.

Then, in his early sixties, his hands began to shake. It was only a familial tremor; it didn’t threaten his health or impair his ability to do a good job once his hands were in someone’s mouth. But the sight of those shaking hands made his patients so nervous he was forced to give up his practice. He and my mother retired to Florida, where he was able to enjoy a good twenty years kibitzing around the pool and playing in daily foursomes of tennis and bridge before he was diagnosed with bladder cancer.

Slowly, he grew too weak to hit a tennis ball and too fuzzy-headed to play out a grand slam at bridge. He started to forget the punchlines to his jokes. Then the middles began to go. He stopped accepting visits from his friends, not wanting them to return home without a laugh. Finally, he refused to speak to my siblings and me when we called on the phone.

I knew he was dying, but I wasn’t prepared for the shock of flying down to Florida and discovering he had lost so much weight he couldn’t keep up his pants. By then, the cancer had metastasized to his lungs, and the nurses set up an oxygen pump in the living room, with a very long tube connected to my father’s nose. Hurrying to use the bathroom, he would undo his belt, which caused his pants to fall. He wore cotton socks, the floor was slippery, and since the oxygen tube kept tangling around his feet, it was only a matter of time before he tripped.

Not to mention he got up so often during the night to use the bathroom that my mother, who’d had two bypass operations and was debilitated by Parkinson’s, was going downhill herself. Against my father’s wishes, I set up a hospital bed in the den. Also against his wishes, I hired a nurse’s aide to help us get through the nights. Until then—the youngest of three, a girl—I had been my father’s pet. I listened to his stories about growing up at his family’s hotel or serving in India during World War II. If I heard a good joke, I would call my dad and offer it as a gift; in return, he would tell me whatever new jokes were making the rounds in Boca.

But he was furious when I set up that hospital bed in the den. He accused me of kicking him out of his “marital bed” so I could sleep with my mother. He refused to believe he got up more than once or twice a night to use the bathroom. And he hated that we were wasting his money on a nurse’s aide instead of keeping it to support my mother. He insisted the aide, a sweet Haitian woman named Michelle, was actually a man, and when she tried to help get him out of bed, he hit her. The wages we were paying Michelle preyed on my father’s mind; he claimed he found a stack of hundred-dollar bills beside his bed, but when he tried to pick them up, the bills kept dissolving. “Why would anyone make money that dissolves?” he cried. “It doesn’t make sense!”

That’s when he heard the carolers. I explained about the lack of oxygen, but the hallucinations were driving him crazy. I always thought losing a parent meant you received a call in the night saying he was gone, after which you underwent a period of intense grief and missed him terribly. I lived in fear some misfortune would befall my son and I would be forced to watch him suffer. But it never occurred to me that I would watch my parents suffer.

In fact, my father suffered so badly that after a while it became impossible to believe he ever had told a joke. Only once, when the hospice doctor visited, did he rouse himself from his hallucinations and put on a final show. He did this, I suspect, because he feared if he didn’t demonstrate the clarity of his mind, the doctor might force him to spend his final days at the hospice center. The doctor, who wasn’t much younger than my dad, led him to the screened-in porch, helped him get comfortable on the lounge chair, then engaged him in a dueling-banjos contest in which the two men tried to top each other in telling dirty jokes in Yiddish while my mother and I marveled at my father’s last performance, his voice clear and strong, not a single muffed word or mistimed line. It was as if a dying athlete had stepped back onto the court and wowed his fans with the powerful serve and forehand that had won him Wimbledon years before.

The performance convinced the doctor to allow my father to remain at home, but he continued to decline, lying in the den, listening to the carolers sing their songs, gasping for air, drifting in and out of sleep.

Until he resumed his dental practice. Eyes closed, arms lifted, he would move his fingers deftly, reaching for an instrument, inserting gauze in a patient’s cheeks, murmuring instructions—turn this way, open wider—or if a procedure was going poorly, shaking his head and muttering. Some people gather so much momentum doing what they have always done they can’t stop doing it even when they are dying. If you were to cut off that person’s head, it would likely keep thinking the thoughts it used to think and coming up with what it used to say—which, in my father’s case, meant telling dirty jokes and instructing his patients to floss more regularly. Most of the time this made him happy. Rather than seeing relatives from his past, he was seeing his former patients.

He grew agitated only when he couldn’t make out the cavity he was trying to fill or see the crown he was installing. “Why aren’t I wearing my glasses?” he would demand, and though his eyes were shut, I would slip his big plastic glasses on his nose, at which he would go back to work. When he would complain the light was bad—“More light! Give me more light!”—I would bend the lamp closer to his face, and he would mutter and nod his thanks, thinking, no doubt, I was one of his loyal assistants from the old days, Mrs. Decker or Mrs. Weyrauch, and he would cheerfully resume his work.

My father’s cry for more light was the funniest, most touching echo of Goethe’s famous deathbed plea that any comic novelist could invent.I was glad my father’s brain was providing him with a dream that allowed him to spend his final days in peace. But dentistry? That was the best his brain could do? I never understood how anyone could be content to be a dentist. Granted, my father used his skills to relieve his patients’ pain. (“A man walks into my office,” he told me once, as if this were the prelude to a joke, “and all he can think about is the pain from his abscessed tooth. I lance the abscess and fix him up, and he walks out the door a new man.”)

But when it came time to choose my career, making sentences seemed more noble and artistic than fashioning a perfect crown, and I wanted a wider audience for my talents than the patients in a small-town practice, the irony being I hadn’t achieved the happiness or success my father had achieved. No matter how many stories or books I published, the rejections made me fear I had chosen the wrong profession and would come to recognize on my deathbed that I had wasted my life in the service of a delusion.

Still, as I sat trying to pass the time while my father practiced dentistry in the air, watching over him in case he imagined himself engaged in a more dangerous hallucination (once, he thought he was being pushed from a moving car and reached out to grab the door, pulling the television down on his stick-thin legs), what else could I do but write? Worse, I was writing a comic novel—and the writing was going well. It was as if I were channeling the sense of humor from my father’s head into my computer’s hard drive.

My only excuse for this theft was that the novel was a tribute to my father. The main character had grown up in the Borscht Belt and was trying to make it as a comic; the working title of the book was The Bible of Dirty Jokes. As is true when any novel is going well, I was living in my characters’ world rather than in the real one; someone watching me might have had the impression I was the one hallucinating.

My father held on longer than predicted, as if he had promised to work his way through the remaining patients in his appointment book before he retired again, for good. The only real crisis came when he decided he had been guilty of practicing dentistry without a license. “Abe,” my mother said, “how could you ever think you’ve been drilling anyone’s teeth without a drill?” But she couldn’t dissuade him from believing the police would show up any minute and haul him to jail, where he would spend his final few days humiliated and disgraced.

Then he became convinced I had sold my novel. Not only that—The Bible of Dirty Jokes had garnered a huge advance. Two million dollars! Now I was set for life. When my mother tried to disabuse him of this new belief, I shushed her. Why rob my father of the joy this delusion brought? Besides, if I ever did sell my book (if not for two million dollars, then for a plausible advance that wouldn’t dissolve in my hands the minute I tried to grasp it), my father would no longer be there to celebrate. Why shouldn’t he go to his grave believing in a truth that eventually might come to pass?

Content in this reassuring new conviction, my father went back to work. And it occurred to me as I watched that it didn’t really matter if you were deluded to pursue some calling. The trick was to engage in a line of work such that, when you were on your deathbed, your greatest peace would come from imagining you were doing what you had done before, all those days and weeks and years. My father’s cry for more light was the funniest, most touching echo of Goethe’s famous deathbed plea that any comic novelist could invent. And even though I have since learned that the etymology of “hallucinate” has nothing to do with luce, I can’t help but think the tacky fifties lamp above his imaginary dental chair provided my father with just enough illumination to implant a perfect crown.

_____________________________________________________________

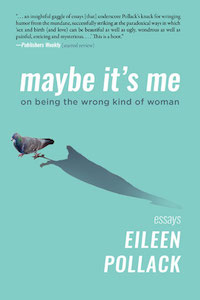

Excerpted from Maybe It’s Me: On Being the Wrong Kind of Woman by Eileen Pollack. Published by Delphinium Books. Copyright © 2022 by Eileen Pollack. All rights reserved.